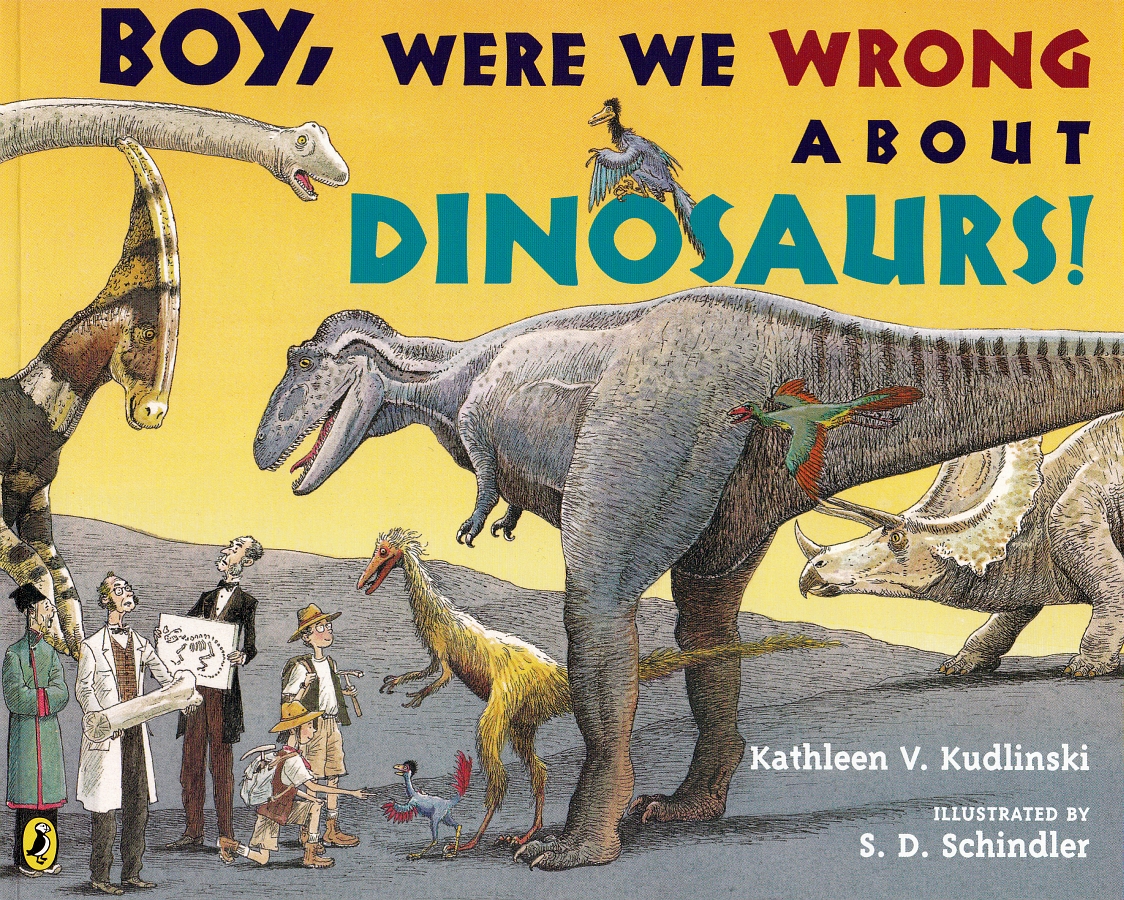

Back in August, I received a couple of books from regular reader Herman Diaz (along with some very fetching duck prints), one of which – My Favorite Dinosaurs – I’ve already reviewed as a pair of Vintage Dinosaur Art posts. I must admit, I’ve been putting off this one simply because it’s an awkward sort of age – as it’s from 2005, it’s not quite old enough qualify for Vintage Dinosaur Art (yes, even by my very loose standards), but it feels a bit too dated for a regular review. Nevertheless, it does deserve a look, especially as Herman went to the trouble of sending it to me. So, here it is, at last – Boy, Were We Wrong About Dinosaurs! And wouldn’t you know it, it’s actually a rather charming little book.

Written by Kathleen Kudlinski (who also wrote Boy, Were We Wrong About the Solar System! and Boy, Were We Wrong About the Human Body! among many, many other children’s books) and illustrated by S D Schindler, BWWWAD (tee hee) has a premise that will instantly appeal to the ardent dinophile. Essentially, it celebrates the progress we’ve all made (but mostly actual palaeontologists, rather than semi-alcoholic bloggers) in dinosaur science by presenting old ideas – which seemed sound, based on the evidence available at the time – and contrasting them with what we now think, based on the new evidence that’s been brought to light. Hurrah! Even better, it’s all presented in a child-friendly manner, with text that’s easy to read and appealing, lightly stylised illustrations of both dinosaurs and people. The cover features a few characters that appear within, including the Victorian man (perhaps Mantell himself?) with his best-guess Iguanodon skeletal, dorky waistcoated scientist fellow, and a happy-looking tyrannosaur who’s just pleased to meat you. Note also that a variety of feathered dinosaurs appear, quite rightly.

My favourite illustrations in the book are actually those that present discredited ideas, such as the sprawling sauropod depicted above. They work on two levels, simultaneously making clear the absurdity of what’s being shown while also being a perfect pastiche of early palaeoart. The above piece is highly reminiscent of a plate that appeared in Hay (1910) (consult SVPOW for more info), while not directly copying it. Although Schindler’s style is mostly quite realistic, there’s enough stylisation to allow for ample character in his illustrations, and the smiling face of the sauropod as it improbably crawls its merry way along the ground does make me chuckle.

In this case, the ‘modern’ illustration depicts a sinister-looking stripy dromaeosaur chasing after some little plant-eating thingies. It’s very ’90s, which is forgivable for a book published in 2005, although the lack of feathers is odd given how much they are emphasised elsewhere. I do like the expression on the dromaeosaur’s face, though; it looks rather pleased with itself.

The choice of a dromaeosaur to illustrate a fast running, post-Dino Renaissance vision of active dinosaurs is obvious and expected, given THAT Bakker Deinonychus. Still, might a large plant eater have made a better counterpart to the ‘sprawling sauropod’ image? Granted, Kudlinski does mention that the skeletons of some dinosaurs “seem to show that [they] were as fast and graceful as deer”, so perhaps a lightweight theropod is a better choice. Perhaps an ornithomimosaur, then? Whatever, I’m just nitpicking. Not everyone is as sick of ’90s-style dromaeosaurs as I am.

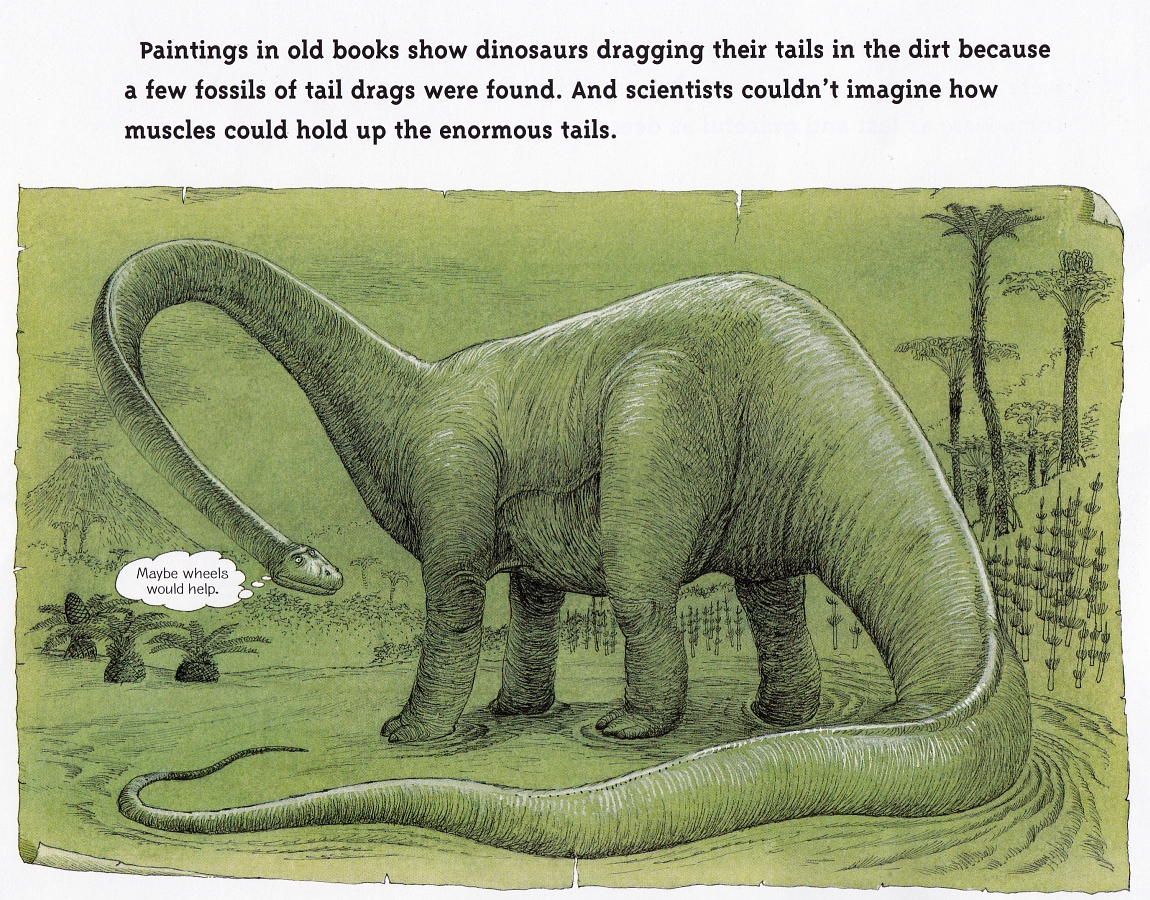

Sauropods are used again to illustrate the old trope of tail-dragging dinosaurs. Again, Schindler doesn’t merely illustrate a dinosaur dragging its tail, but also includes extra details to make the image appear suitably like early-to-mid-20th Century palaeoart, from the obligatory volcano to the entirely static, tree-trunk legs of the animal. I’ve included the text here, too, because I’d like to draw attention to the fact that Kudlinski specifically mentions how “scientists couldn’t imagine how muscles could hold up the enormous tails”. It rather reminds me of that crank who wrote a book that was somehow published by HarperCollins. Remember him?

Of course, Kudlinski is quick to point out that

“Thousands of fossil footprints have now been found with no tail drag marks at all. Clues in some dinosaur fossils show that their tailbones had stiff tendons inside to hold them out straight.”

Cue the above illustration of Tyrannosaurus, walking proudly with its tail aloft. Although stylised, I still think it looks rather awkward, mostly around the head and neck, which seem to pay little regard to how the animal would fit together. There’s also the matter of the tooth row extending under the orbit, which is kinda weird. For whatever reason, the head reminds me of Mark Hallett’s famous Tyrannosaurus painting, Awakening of Hunger, from way back when. It’s probably the hint of dorsal spines. It does get the point across plenty well, of course, and I’m really impressed that the book takes the time to mention why scientists no longer think that dinosaurs dragged their tails, even if it’s brief. This is a step beyond the ‘here’s a dinosaur, it had big teeth, it lived 100 million years ago’ school of children’s dinosaur books, instead making it clear that scientists’ changing ideas are based on solid fossil evidence. Good stuff.

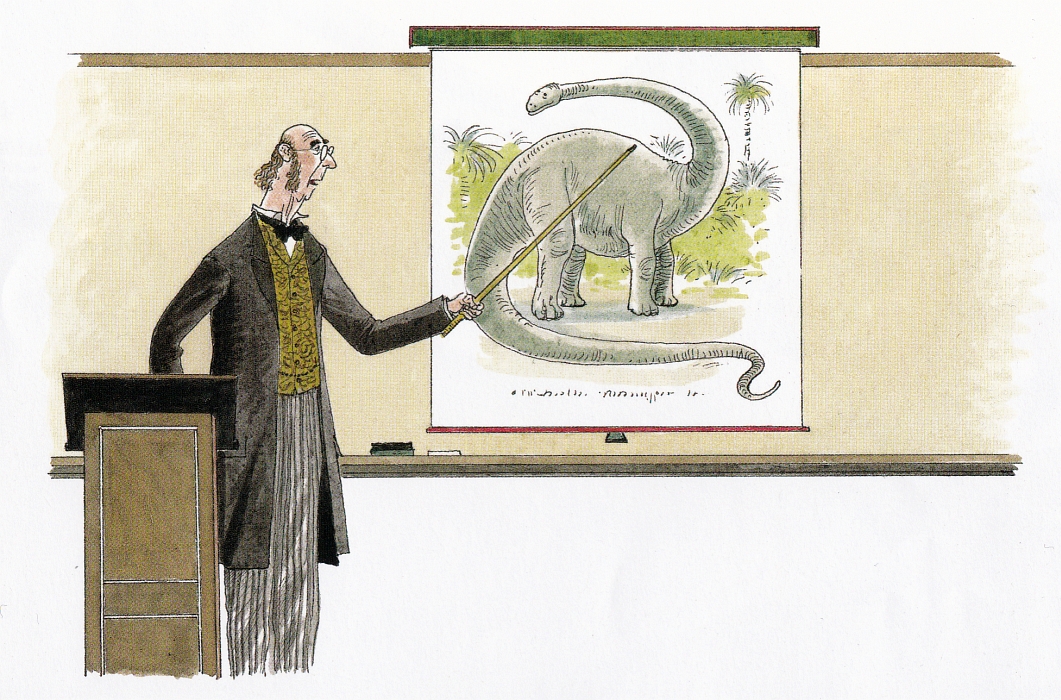

And now, I must mention what’s surely my absolute favourite illustration in BWWWAD, just because it’s so inherently amusing (to me, anyway) – an ageing, muttonchopped academic in a snazzy waistcoat and bow tie, engaged in a Very Serious lecture that involves a slide depicting a sad, grey sauropod. Kudlinski’s point here is that “scientists used to think that large dinosaurs were grey, like today’s grey elephants,” but that study of their skulls and, especially, braincases indicate that they were very visually-orientated, as are many of their living relatives. So, it’s likely that even very large dinosaurs would have had colouration much more complex than today’s large mammals, whether for display or camouflage. As I’ve already said, it’s lovely that this evidence is mentioned in a kid’s book – I’d compare it to when Planet Dinosaur brought on fossils and explained the evidence, rather than simply presenting CG dinosaurs to us.

Representing the new, more colourful dinosaurs is this Parasaurolophus, decked out in excellent cryptic camouflage. I like that the idea of dinosaurs being more colourful than previously thought is used in the context of camouflage, rather than just being an excuse to dazzle us with bright colours, and Schindler’s illustration is very attractive in a Kishian sort of way. Look – a forested environment with varied plant life AND uneven, sloping ground! These things shouldn’t be half as impressive as they are. The dinosaur is rather noodle-necked, but this is from 2005, after all. Surely my second favourite piece, after the waistcoated lecturer guy.

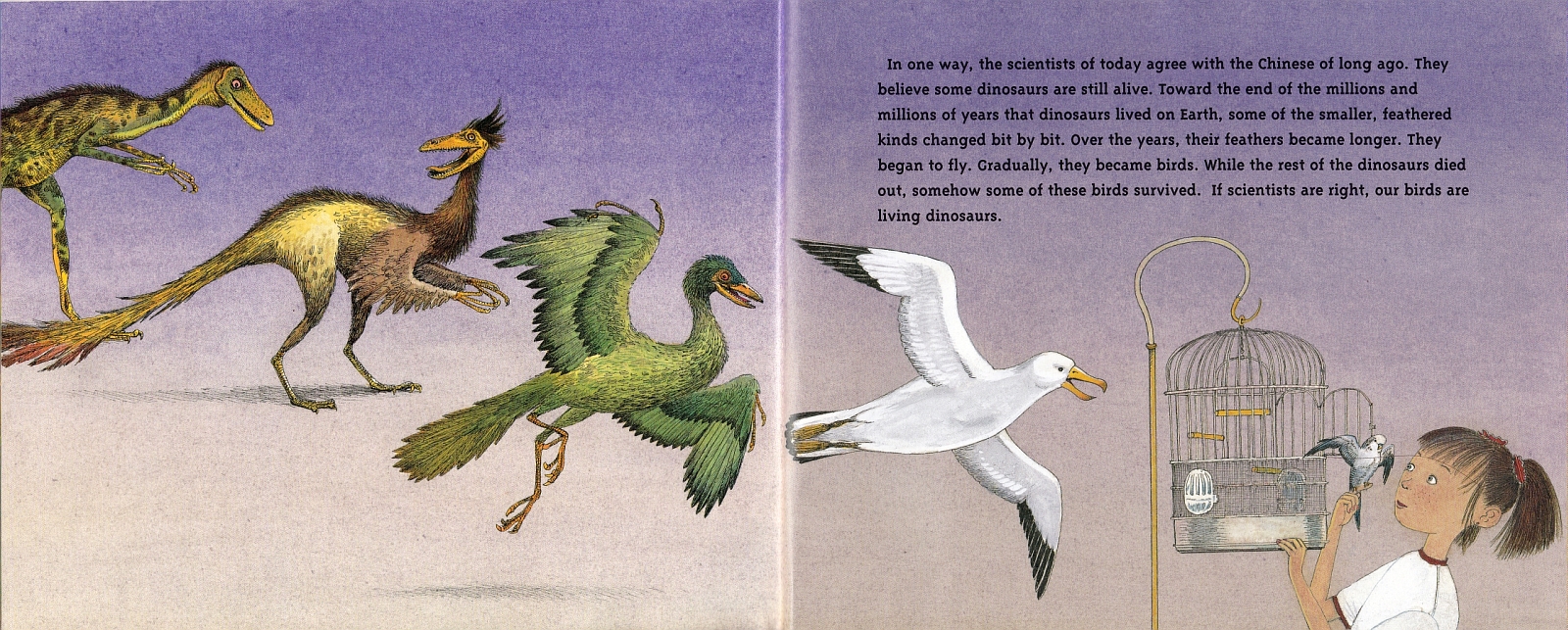

A good indicator of BWWWAD being a 2005 kids’ dinosaur book worth its salt is the inclusion of feathered dinosaurs. Kudlinski isn’t as confident here as she might have been – although I speak with the benefit of 13 years of hindsight, of course – but nevertheless, Schindler provides plenty of illustrations of highly birdlike feathered dinosaurs. It’s not clear which species they are supposed to be, exactly, but a few (including the animal in the centre of the above illustration) resemble an old Dorling Kindersley-commissioned model of Caudipteryx, as Darren Naish (the very same) pointed out over on Facebook. As befits the slightly fanciful style of the illustrations, the dinosaurs here are talking to each other. Amusing, but it also gets kids thinking about why feathers might have evolved – both for insulation and display.

And finally…Kudlinski explains how feathered dinosaurs became today’s birds, with a nice accompanying illustration by Schindler. It’s a delightful evolutionary series ranging from the slightly mangy-looking Mesozoic theropod, to the tiny parrot cruelly confined in an ornamental cage by a sadistic human child. (I kid – it’s a lovely piece.) Kudlinski further wraps the book up very nicely by referring to its beginning, where ancient Chinese workers are depicted exhuming ‘dragon bones’ which they believe belong to animals that must still be alive, somewhere. The idea that we are now able to relate those fossil remains to real living animals, that are all around us, is suitably thought-provoking and awe-inspiring. Here’s another wonderful little testament to the hard work of palaeontologists, and I’m glad that Herman sent it over to me.

3 Comments

Dino Dad Reviews

November 29, 2018 at 5:22 pmVery nice review! Mine wasn’t nearly so well thought out as this, though it WAS only the third book review I’d ever written.

Thomas Diehl schreibt: Sieben am Sonntag 02.12.2018

December 2, 2018 at 2:18 pm[…] Das Blog Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs hat letzte Woche ein interessantes Buch vorgestellt. Ich selbst hatte schon eine ganze Weile diese Idee, ein Buch zu verfassen, das den Leser durch die seltsamen Bilder führt, die sich die Menschen über die Jahrhunderte von jenen Wesen gemacht haben, die wir heute als Dinosaurier kennen. Von dem für ein menschliches Bein gehaltenen Riesensalamander über Meeresreptilien, deren Kopf versehentlich auf den Schwanz montiert wurde, bis zu Stegosaurus, einem Dinosaurier, der im vollen Bewusstsein dessen benannt wurde, dass sein Name sich auf eine komplett falsche Vorstellung des Tiers bezog. Es ist alles so herrlich seltsam. Kathleen Kudlinski hat bereits 2005 eine ähnliche Idee umgesetzt und das Ergebnis ist Boy, were we wrong about Dinosaurs. Es ist Teil einer ganzen Reihe von Büchern dieser Art, deren andere Bände sich beispielsweise mit Medizin, dem Sonnensystem oder Meteorologie beschäftigen. Die Bücher sind alle lesenswert und bieten schöne Beispiele dafür, wie sich die Wissenschaft mit der Zeit die Welt erschließt und wie sie ihre Erkenntnisse gewinnt und stetig mit neuen Entdeckungen verbessert. […]

Luis Miguez

January 10, 2019 at 2:48 pmIt seems an amusing and fresh book, indeed