Sometimes you catch a scent and can’t drop it. My bloodhound mode was activated by a recent email from Carl Mehling of the American Museum of Natural History, asking if we knew what the earliest children’s book on dinosaurs.

If I’m not mistaken, the earliest book we’ve written about which was purely intended for children is Hilary Stebbing’s Extinct Animals (read Niels’ 2020 post and listen to the podcast episode). Its 1946 publication date beats Roy Chapman Andrews’ juvenile-aimed dinosaur books by about a decade. In our LITC group chat, Natee said that they may also count Henry Knipe’s 1912 Evolution in the Past (featured on the most recent podcast episode). The development of children’s literature is fascinating and you can’t expect early titles to confirm to modern norms, for sure.

I began explore the catalogs of various children’s literature collections. I came across prehistoric-themed titles from the turn of the 20th century, but they didn’t deal with dinosaurs at all; it seems there was a serious Cave Man fad a hundred and twenty years ago. But one search led me to The Red Book of Animal Stories, published in 1899 and thankfully digitized by the University of Florida’s George A. Smathers Libraries. It’s part of Andrew and Leonora Blanche Lang’s Fairy Books, a series of 25 tomes collecting fictional and true stories to thrill and delight the young reader. One of the primary illustrators of the series was Henry Justice Ford, and he has a few paleoartistic treats for us.

The cover of The Red Book of Animal stories. I love that the little girl is gleefully reading as the little boy cowers in abject fear. Progressive! Image obtained from University of Florida Digital Collections.

These pieces appear in the chapter “The World in its Youth.” It is a quick distillation of 1899’s paleontological status quo, predictably marred here and there with casual racism. But it’s not without merit, especially in Lang’s description of evolution as a natural process. He clearly aims to widen the reader’s point-of-view and instill the humility that comes along with really, really pondering the long history of life on Earth.

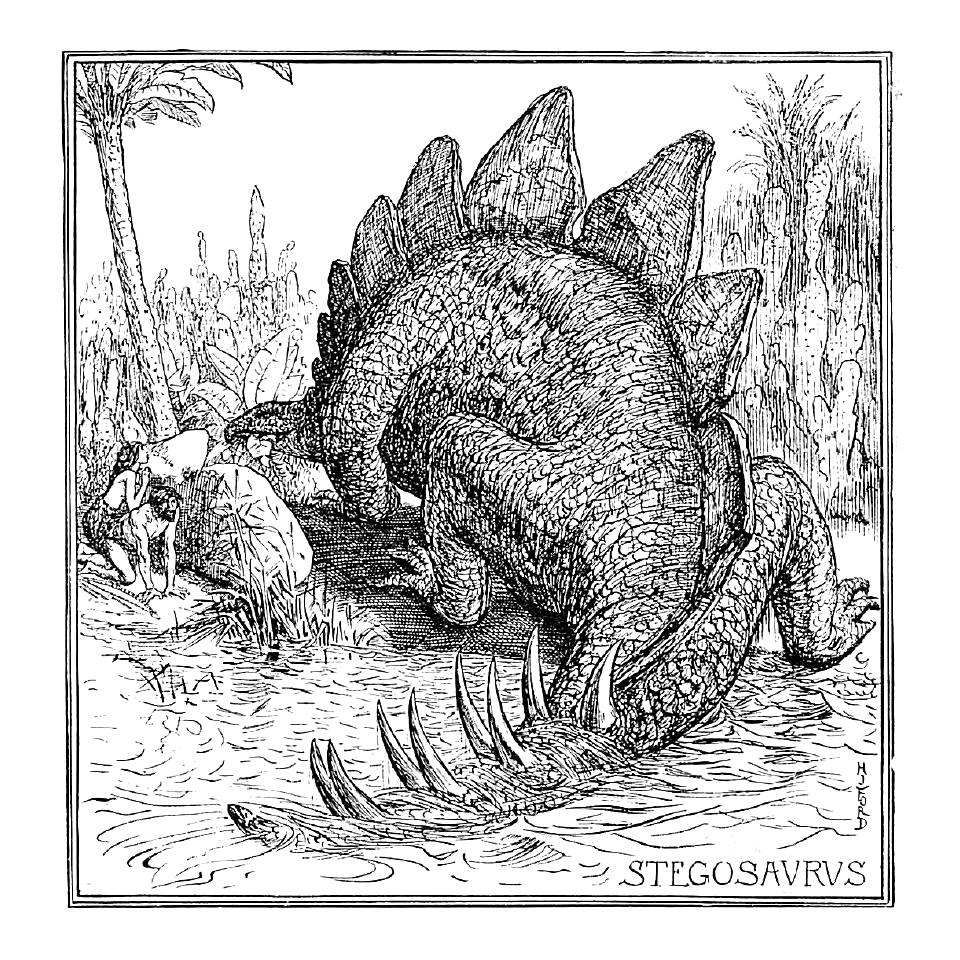

We’ll start in our home turf of the Mesozoic, with a sprawling hulk of a Stegosaurus. The anachronistic people, looking like Edenic outcasts, seem to be Ford’s own flight of fancy. Lang’s text makes it clear that the dinosaurs predated the noble genus Homo by quite a long time. Lang names Hutchinson’s 1897 Extinct Monsters as a source for his writing, and it’s refreshing that Ford didn’t simply copy Josef Smit’s illustration from that book.

Henry Justice Ford’s Stegosaurus with anachronistic companions. Image obtained from University of Florida Digital Collections.

Next is a less elaborate illustration of a pterosaur, though what it lacks in scenic detail it just about makes up for in pure mischievous character.

And that’s it for the Mesozoic. It’s unfortunate, as Lang’s prose teases us with descriptions of Brontosaurus, Archaeopteryx, and post-Bernissart Iguanodon. I’d love to see what Ford would have done with them.

Ford does offer us a peek into the Pleistocene with a pair of shaggy megafauna. First, we have another hapless group of humans contending with their titanic neighbors: a pair of trunked Megatherium browsing for dinner have intruded upon their domestic bliss. That cozy little dwelling is not long for this world. But just look at the fur on that sloth’s arm! Again, I long for an entire portfolio of Henry Justice Ford paleoart. This stuff is just magical.

Henry Justice Ford’s amusing illustration of giant ground sloths making life difficult for a trio of Homo sapiens. Image obtained from University of Florida Digital Collections.

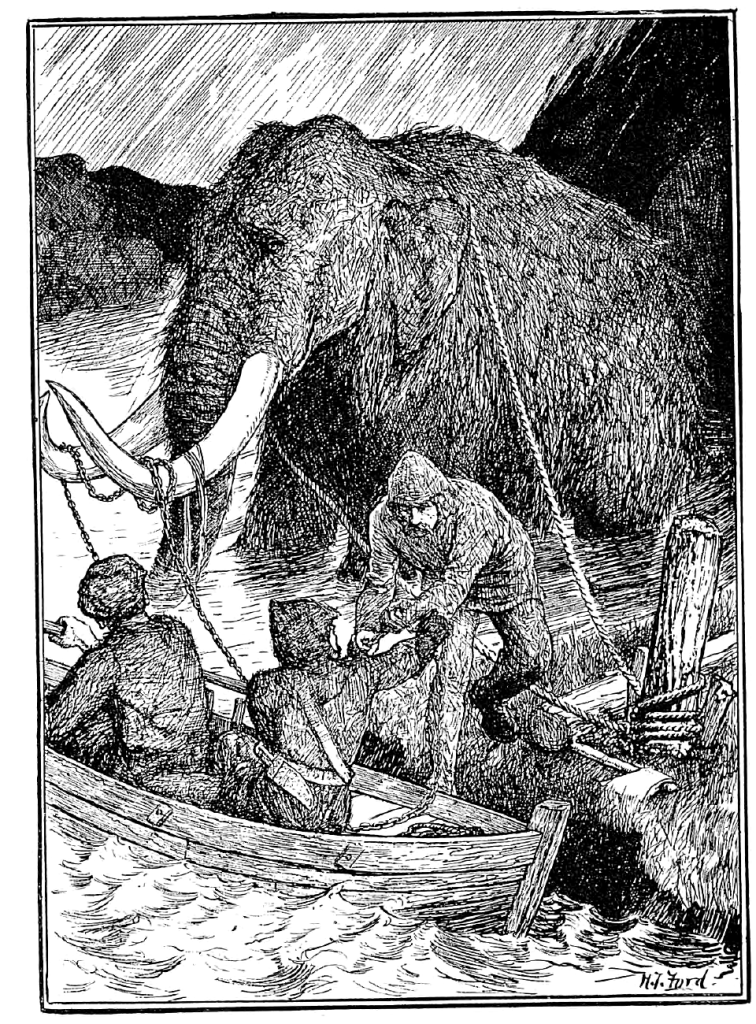

Eventually, humans sort out the crafting of garments. More importantly, they sort out how to fell the great beasts who share their world. This scenario, like the Megatherium illustration, is not referenced in the text, suggesting that Ford was given generous artistic leeway. Here again, the fur is rendered so well you can just about feel it. You certainly feel for the poor proboscidean.

Henry Justice Ford’s illustration of a mammoth hunt. Image obtained from University of Florida Digital Collections.

Ford clearly loved drawing dramatic and humorous situations. Maybe we can chalk up those Jurassic humans to artistic enthusiasm overriding the pursuit of scientific veracity. Or maybe the editorial hand was so light, he wasn’t instructed otherwise.

One last image deserves a look, the mythical beast Odenthos. You can’t help but wonder if Ford was inspired by Hawkins’ Crystal Palace sculptures when conjuring this one. What’s an Odenthos? I don’t know, other than a large three-horned animal. Seems to be an Old French term.

Henry Justice Ford’s illustration of the mythical saurian beast Odenthos. Image obtained from University of Florida Digital Collections.

Of this mysterious French monster, Lang writes:

There is no time to tell of all the strange monsters that men used to invent just to frighten themselves! There was a creature called the Odenthos, which had three horns instead of one, and felt a special hatred of elephants.

So maybe the mammoth above got off easy.

I intend to stay on the trail and already have a handful of books to write about in 2023 (this site has some intriguing leads, though it is strictly focused on American literature). In the meantime, if you have any knowledge of 19th or early 20th century children’s dinosaur books, children’s literature collections worth exploring, or what the heck an Odenthos is, please leave a comment below.

7 Comments

Mark Witton

December 12, 2022 at 12:32 pmI don’t know if they’re the oldest, but some books to look into are “Peter Parley’s Wonders of the earth, sea, and sky” (c. 1840), which has a significant palaeo and geological component even if it’s a more general natural history tome. “The Fairy Tales of Science: A Book for Youth” (1863) is similarly broad in scope but has a chapter devoted to “The Age of Monsters”. “The Fossil Spirit; a Boy’s Dream of Geology”, from 1854, is devoted to palaeo and geology, so might qualify as the only true “dinosaur book” of these – obviously accepting that “dinosaur books” weren’t really around yet – the best you could get was a book about the evolution of life in general in the 1850s. All are illustrated to a certain extent, but they’re very wordy compared to modern children’s books. You can find them all online easily as well – Google Books etc. have digitised copies.

David Orr

December 12, 2022 at 2:39 pmThanks, Mark. I’ve got Peter Parley and will definitely look up the others! Some of my coworkers at the rare books library where I work also wondered if any London publishers printed books for younger readers around the Crystal Palace exhibition, have you come across any of those?

T.K. Sivgin

December 12, 2022 at 2:44 pmI have a strong suspicion that Odenthos is an alternative name for Odontotyrannos, a three-horned Indian monster that appeared in medieval books and retellings of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the region. It likely was a very distorted account of the Indian rhinoceros.

David Orr

December 12, 2022 at 9:07 pmYes, that seems very likely!

paleocharley

December 14, 2022 at 11:29 amPerhaps related- I believe Herodotus mentions the (?Indian) rhinoceros technique of gutting elephants. Also, Darren Naish, in one of the incarnations of his Tetrapod Zoology blog, has an article on the occasional third horn of rhinoceroses. Unfortunately, apparently, the only recorded cases are in the 2 (or 3) African species.

Great review as usual, David. (Damn, now here’s ANOTHER one that I need to search for…)

David Orr

December 14, 2022 at 12:01 pmYeah, it has that flavor of “one time someone saw an elephant run away from a rhino and the story got blown up to epic proportions.”

paleocharley

December 14, 2022 at 11:32 amPS: If I recall correctly, “Odenthos” would mean something like “toothed beast” in very BAD Greek.