Here we are again with Verdwenen Werelden, Marie Hubrecht’s masterpiece and the gift that keeps on giving. As we always do, we’ve started off by showing you all the dinosaur stuff. Then, we went to the more recent past to look at some mammals. That leaves us with the many depictions of marine life Hubrecht put onto canvas with gouache, panache and all the homebrew passion of a determined amateur. Let’s, ahem, dive in.

This is actually the very first image in the book. It is an “allegorical depicition” of the formation of the continents, out of volcanic activity. You might have noticed from the previous parts that Marie Hubrecht loved herself a nice, old-fashioned smokin’ volcano. I chose to show this piece to illustrate this book’s holistic approach to explaining the history of the natural world: not just the animals, not just the plants, but the geological processes too. The second picture (which I didn’t get a scan of) is quite similar, and it’s not until a few pictures in that we actually see some animals.

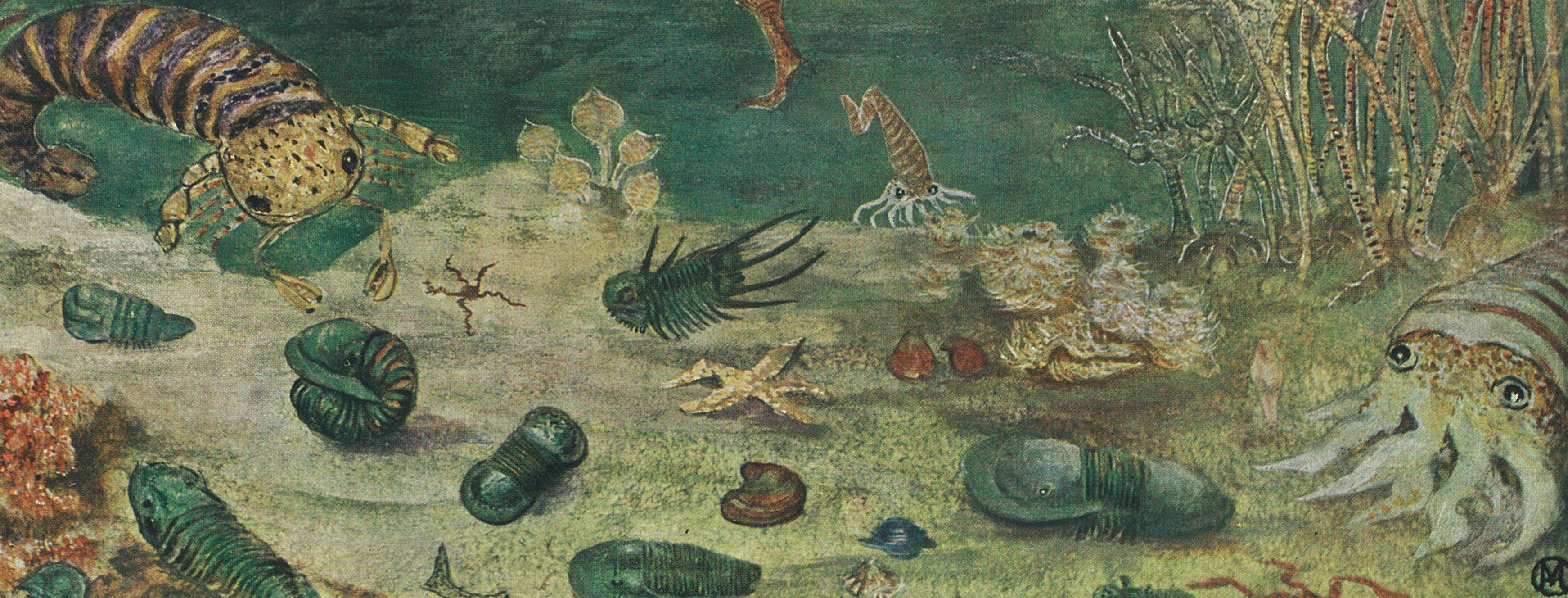

Here’s a Silurian sea. Once again, it’s busy as all get-out; the accompanying text identifies over 50 different species depicted in this painting alone (and it’s one of two Silurian pieces). Was there ever anyone before Maria Hubrecht who spent so much time and effort making such a comprehensive ecyclopaedia of extinct animals, while painstakingly illustrating so, so many of them? The trilobites alone!

The two that caught my attention, of course, are the giant “sea scorpion” Pterygotus and the giant, adorable Orthoceras in the lower right corner. In terms of cuteness, Hubrecht’s big-eyed ammonites are well up there. However, the cutest animal here has to be this darling Trococeras. Look at ’em go, tripping along on those tiny tentacles!

On to the Carboniferous/Permian border, to a particularly gloomy and foreboding sea. And here’s the first tetrapod in the book! Excuse my unapologetic vertebrate bias, invert fans, but at least I admit it, right?

And what a tetrapod it is, this Mesosaurus with its staring eye. As a scientific reconstruction it may not hold up that well, but it’s certainly cool. In a more “Where’s Wally” vein, another mesosaur, Stercosternum. is hiding among the corals in the lower left. And hiding is appropriate, because this genus is so obscure that Googling it yields only seven results (I guess this is the eighth now).

Janassa, Palaeoniscus, Pleuracanthus

Another cool little animal, painted stylishly and minimally with only some subtle streaks of black, is the mysterious fish on the right here – a prehistoric shark of some kind – identified as Pleuracanthus. The fish that once was given this name must have had a name change, because I found the genus Pleuracanthus to be occupied by – what the heck else – a beetle. I have no idea if the shark has been renamed. I also find my eye drawn to the peculiar translucent, ray-shaped fish. It’s called Janassa, and based on some schematic illustrations by Otto Jaekel. Hubrecht was probably the first to restore this animal inside an environment.

Here’s a more colourful piece, though there’s still a gloomy vibe to it. These are Jurassic seas and Hubrecht takes this opportunity to explain, at some length, the convergent evolution between dolphins and ichthyosaurs. The big ones are Stenoptygerus on the left and Eurhinosaurus on the right. Compared to the ichthyosaurs, a brightly-coloured Lepidotes fish has probably been made too gigantic.

Many lovely freaky fish in this one. My favourite is this dark, shadowy shape with five spots, as if they are eyes. This is Squatina, an angelshark, not an animal that is typically made to look this sinister.

Top Left to Right: Aspidoceras, Coccolepsis, Eurhinosaurus (head), Spiroceras. Bottom Left to Right: Aspidorhynchus, Parapatoceras, Artriticus

Hubrecht also shows a great variety in ammonites: Aspiodoceras with its spiky shell, Spiroceras with its extremely thin shell, and Parapatoceras which is, according to Hubrecht, “shaped like a question mark”. How many modern prehistory books for a general audience show this much ammonite variety?

Apart from the ichthyosaurs, Hubrecht hasn’t shown many marine reptiles so far, but there’s a fair few here in the Cretaceous sea. The Elasmosaurus, grabbling a belemnite, is immediately recognizable. It’s pretty far out there, but as far as vintage plesiosaur reconstructions go, this one is still low-key. We find Archelon in the lower right, hanging out with an ammonite that must be ridiculosly gigantic.

Tylosaurus and Platecarpus

Plioplatecarpus

Rather conspicuous in its absence is Mosasaurus hoffmani, the most famous and prominent prehistoric animal found in the Netherlands. She does mention it (as well as the fact that those accursed French stole it from us) but opts to illustrate Tylosaurus, Platecarpus and Plioplatecarpus instead (the latter is also known from the Netherlands). The mosasaurs are interesting in that they don’t resemble the usual vintage mosasaur paintings at all. You know the ones; ridge backed, serpentine sea dragons, doing battle with knotty-necked plesiosaurs mostly above the surface of a stormy sea. Hubrecht is having none of that; these depictions remain naturalistic. I have no idea who or what they’re based on, or if she made them from whole cloth.

Here’s something interesting. One of the ammonites is swimming upside down. The way buoyancy mechanics work, ammonites would have swam with their faces poking out from the bottom of their shell, but that isn’t obvious to everybody. In fact, if you look at Hubrecht’s original Amsterdam murals, all the ammonites are consistently upside down. One of the experts she met must have corrected her, and nearly all ammonites in the book are rightside up, except this one. Was this her little joke or a mistake left in?

This is the only aquatic Cenozoic scene in the book. It’s a rather lovely composition of mountains, shores and sea, showing a variety of extant and extinct species. The birds are all penguins, gulls and pelicans, there’s some pinnipeds in the far distance. In the text, our eccentric Great Aunt Marie muses on the intelligence of penguins, who she considers to be highly humanlike. She amusingly wonders if they are having a meeting of the bird union. Sure.

The whales are who really take centre stage here. Most of them are identified as Balaenoptera, the genus of the fin whales and the blue whale, but Hubrecht makes them look more like sperm whales. Oddly, they are not depicted as particularly large. The large toothed whale in the front is identified simply as “Delphinidae”, the text does not clarify what it’s supposed to be. A goof is that some dugongs are depicted as going on land, which the text insists is something they can do.

This shark, oddly depicted from the ventral side, is meant to be none other than the infamous megalodon. It is simply referred to as Carcharodon, the genus of the great white shark, but the text makes it clear that we’re looking at its gargantuan, whale-devouring, Statham-fighting cousin here. It doesn’t look particularly huge, but I suppose neither do the whales. Joschua has told me the picture is based on Othenio Abel, but I have not seen the original. Even more interesting are the thin, elongated dolphins that surround megalodon, identified as Cyrtodelphis. Once again a highly obscure animal, but a very cool one.

And that’s Verdwenen Werelden, the work of a determined woman who didn’t let a lack of formal education in art or science stop her from making evocative and unique palaeoart. If it wasn’t obvious by now, I have in the process of researching and writing this review become quite a big fan of Maria Hubrecht, and I would love for her work to be more widely known. While the book, at the time, wasn’t as influential as Hubrecht had hoped, it is not too late for her life and work to be a source inspiration for artists today.

Thanks to Esther van Gelder, Dicky van de Zalm and Ilja Nieuwland for sharing some of their research, and to Joschua Knüppe, Mark Witton and our beloved Marc Vincent for their keen eyes for spotting copied palaeoart.

7 Comments

Thomas Diehl

March 23, 2020 at 4:07 amPleuracanthus has indeed been renamed, namely to Xenacanthus. Oddly, this happened in 1848, so I have no idea how the old name ended up in this book.

Niels Hazeborg

March 23, 2020 at 4:49 amIt would have been a question of what information was available to whom at that point in time. Brontosaurus is also in this book, and that wasn’t a valid genus at the time.

Damian

March 23, 2020 at 5:47 pmStercosternum is probably a typo. There is a mesosaur named Stereosternum!

Niels Hazeborg

March 24, 2020 at 6:12 amI cheked the book agan to see if I misread. But no, you’re right. It’s a typo. Unfortunately Google didn’t correct me when I looked for “Stercosternum”. XD

ED

March 24, 2020 at 12:26 pmPlease allow me to apologise for not being able to send this as an email, but my service has refused to recognise the email address given on the front page as valid and so …

Now I have been a fan of LOVE IN THE TIME OF CHASMOSAURS for some years now (please allow me to thank you for all that entertainment & edification!) and recently stumbled onto a possibly-interesting subject for a future chapter of VINTAGE DINOSAUR ART, to whit a comic book adaptation of Mr L. Sprague de Camp’s A GUN FOR DINOSAUR (a most entertaining short story that I can thoroughly recommend to those who enjoy Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s THE LOST WORLD and similar fare). I most happily recommend both these versions of the same story to you and hope you will enjoy them even if they do not inspire a future article.

Keep Well and please do keep up the Good Work!

https://hell.pl/szymon/Baen/The%20best%20of%20Jim%20Baens%20Universe/The%20World%20Turned%20Upside%20Down/0743498747___8.htm

https://marswillsendnomore.wordpress.com/2012/06/21/a-gun-for-dinosaur/#jp-carousel-18881

^^ The first link will lead you to the original short story, the second to that adaptation. ^^

Ilja Nieuwland

March 28, 2020 at 8:06 amI think the “snakey” Plioplatecarpus might be inspired by image XIII (between p. 36 and p. 37) in Henry Neville Hutchinson’s “Extinct Monsters” from 1905. See https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42584/42584-h/42584-h.htm. Also, there is a similar illustration near the Mosa skull in Teyler’s Museum, but as with everything in that place there’s no telling if that was already there in the 1920s, even though it looks it might have been.

Grant Harding

March 31, 2020 at 12:47 pmThat formation of the continents picture is gorgeous.