While my previous post on this book focused on the work of someone who is an acclaimed wildlife artist – but not a dinosaur specialist – it should be noted that Ranger Rick’s does feature rather a lot of work from some Big Names in palaeoart, especially Mark Hallett and Ely Kish. Most of the Kish pieces have been featured on this blog before (often multiple times, including in David’s 2010 post), so I thought I’d take a closer look at Hallett’s illustrations here. It does help that Hallett is one of my favourite palaeoartists of all time…perhaps my absolute favourite. (Perhaps.)

Hallett’s palaeoart is highly detailed and tends towards the realistic, but when compared with modern attempts at ‘photo-real’ palaeoart, it’s definitely stylised. That’s no bad thing. Hallett’s work always achieves what should be the ultimate goal of palaeoart – to make us believe we are looking at a living, breathing creature on our planet, and not some fantastical sci-fi monster. While his work would improve enormously in the 1990s and beyond, even in the 1980s, he was still streets ahead of many of his contemporaries.

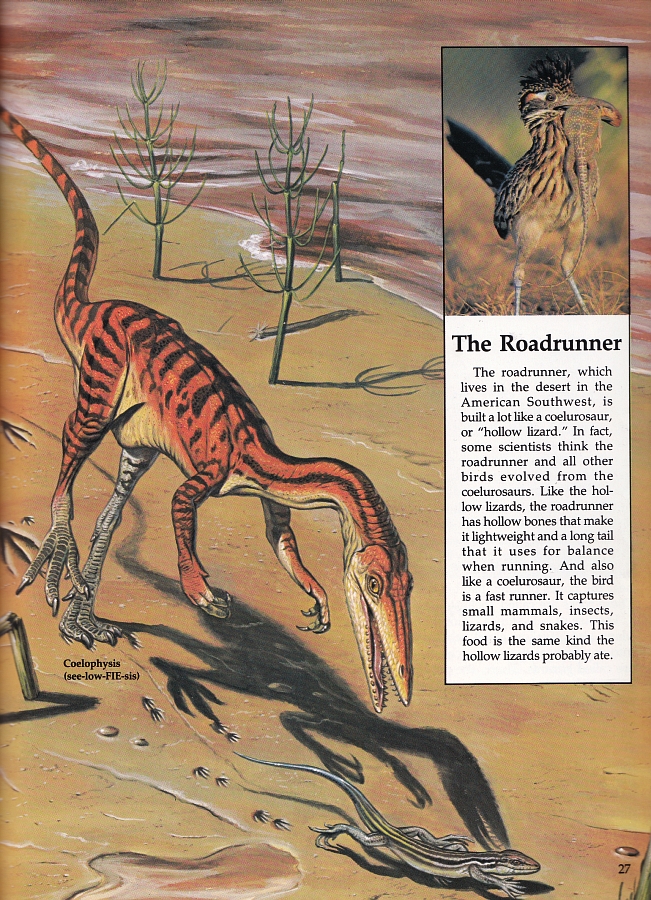

Hallett’s Coelophysis (above) contrasts with the gawping, awkward-looking Sibbick version from the Normanpedia (published a year later than this) in being sleek, birdlike and much more ‘modern’ in appearance; it would almost pass muster today. It’s very ‘Paulian’, for sure, but Hallett’s dinosaurs always seem much more three-dimensional, and their convincing character lies in countless small touches that few artists are able to pin down. It’s there in the gleaming, beady eye, the subtle flexion of the toes, the expertly placed skin folds on the neck, and the careful attention to anatomical detail. Give or take a few nitpicky details we’d change these days (tail’s a bit thin, stick some lips on), this Coelophysis just seems to work as a living creature.

And the stripey skin looks pretty cool, too.

You’ll note that Hallett is fond of sticking tarsal scutes on his theropods, that is, birdlike rectangular, flat scales on the toes. This always reminds me of a blog post from Matt Martyniuk (seven years ago!) in which he considered whether or not this was merely an unwarranted palaeoart trope, and mentioned Hallett specifically. It’s to do with bird scales really being modified feathers (genetically speaking), and all that jazz. However, someone then mentioned Concavenator, an allosaur with honest-to-goodness birdlike toe scutes, which did knock him sideways a bit. Still, it remains an interesting discussion of a palaeoart convention and how justified it might be. As an aside, I’m quite sure that Hallett’s scuted-up non-avian theropod feet are directly linked to JP‘s T. rex having just such feet, especially as Hallett produced concept art in the film’s early stages of development.

Do birdlike scutes belong on the toes of a non-tetanuran theropod like Ceratosaurus? Possibly not, but there they are anyway. Suck it, haters. Again, Hallett’s reconstructions are wonderfully up-to-the-minute for 1984, and must have looked revolutionary to contemporary children raised on palaeoart based on Zallinger and Knight; indeed, these would have enthralled me as a kid in the early ’90s. Ceratosaurus looks muscular, is posed horizontally and has the correct number of horns on its head (even if two of them might be a little far back). It also has those fantastic Hallett theropod feet going on, which somehow just always look so uniquely convincing. (I might have a thing for theropod feet.)

Stegosaurus, meanwhile, appears alert, its head and tail held well off the ground. It’s marvellous stuff for 1984. The animals’ skins are stretched and creased and floppy in places, but mostly convey an impression of fine dinosaurian scales, as they should. It sounds ridiculous, but so many contemporary artists persisted in giving their dinosaurs proportionately huge scales (obviously with an eye on modern lizards) or elephantine, gnarly, wrinkly skin seemingly devoid of scales at all.

What I’m saying is, Hallett knew his stuff. He knew his scales. And he could pull of a neat dappled camouflage pattern, too.

Hallett was also responsible for Ranger Rick’s inevitable depiction of two headbutting Pachycephalosaurus. Giving these guys tarsal scutes might be pushing it, but then with all the quilled ornithishians about these days, who knows anymore? As usual, the pair of “boneheads” is battling it out in a very flat, arid landscape – Bernard Robinson (among others) painted much the same scene. I’m not sure where it originated, but it’s an interesting trope nonetheless. Pleasing little touches abound again here, such as the pads on the animals’ feet, the differing scalation on the lower leg, the small flecks of spittle emerging from one animal’s mouth, and that totally rad yellow X pattern.

They do look a little like their hips might be too narrow – a common mistake in pachycephalosaur art, for the animals had rather wide hips to accommodate their voluminous herbivorous guts. But as it’s a lateral view, it’s hard to tell. We’ll let you off this time, 1980s Mark Hallett.

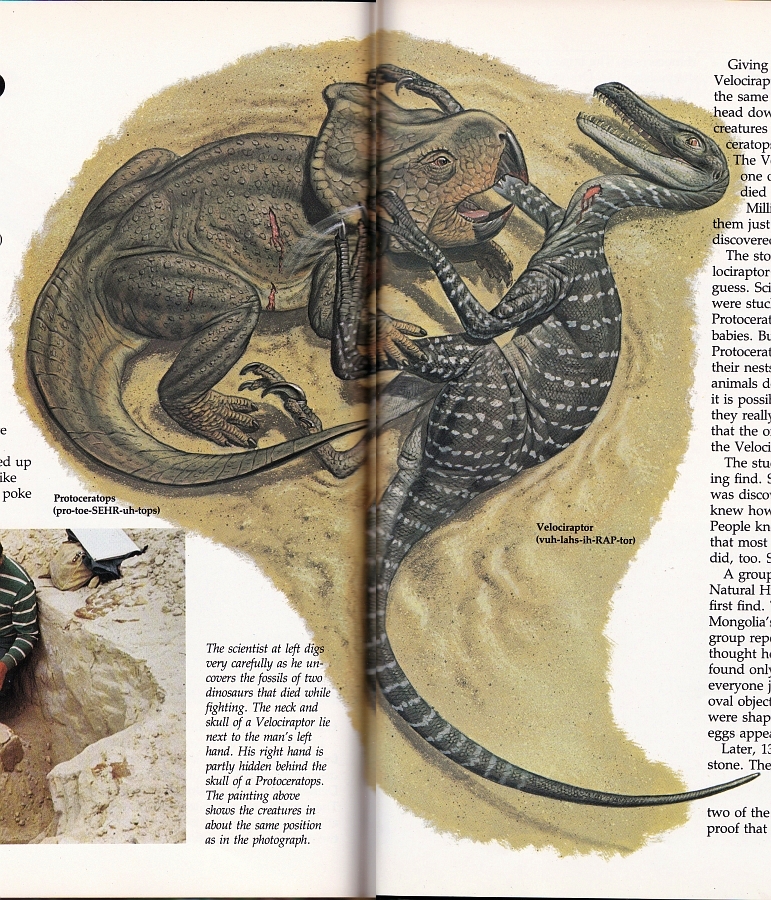

The Fighting Dinosaurs are also illustrated by Hallett, and his Velociraptor is about as good it got in 1984. Velociraptor is scaly, of course (as was the style at the time), but it’s interestingly depicted the almost uniform fine scales so typical of dinosaur skin, whereas Protoceratops receives larger knobbly bits and tough-looking, almost crocodilian scales on its face (they might even really be cracked keratin, as seen on actual crocodilians). One is given the impression of the herbivore having a toughened hide to protect itself, although bludgeon-headed Protoceratops would have been a formidable opponent for Velociraptor in any case (which is one reason this fossil’s so fantastic).

That stripey pattern on Velociraptor is, again, very natty, and I’m sure it’s reminiscent of a certain lizard that I can’t quite remember just now. Please feel free to chime in, herp-people.

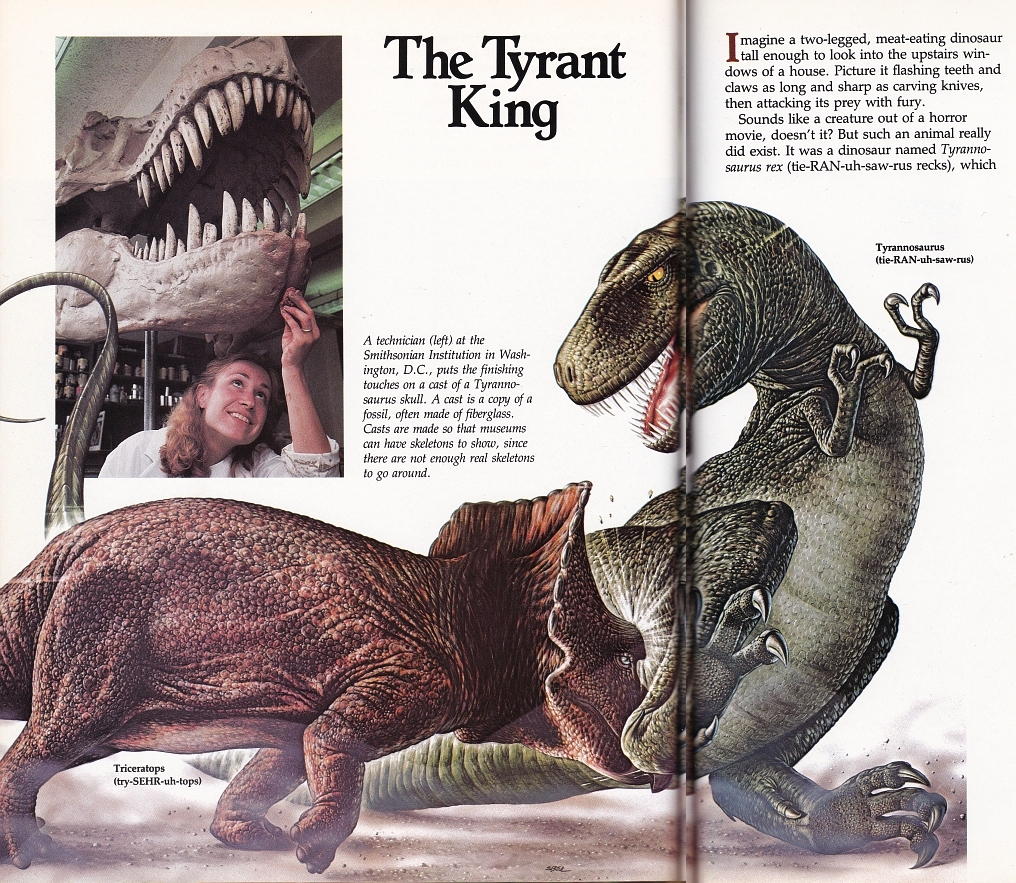

If you’re thinking that the above piece doesn’t look much like a Hallett, that’s because it isn’t one. But I can’t just go on about Hallett and sexy theropod feet all day. This illustration of Triceratops stabbing Rexy in the thigh (yet again) is by Alex Ebel, and apparently originated in Childcraft – The How and Why Library in 1982. Sounds like something to hunt down.

A few things strike me about this scene. Firstly, those scales are wonderfully done, and the Triceratops in particular has a convincingly solid, hefty feel to it thanks to some lovely shading and (mostly) good attention to anatomical detail. Rexy is rather more awkward-looking, sporting slightly strange hooked fingers, a somewhat pear-shaped body, and a massively long lizardy tail. Also, the scene is oddly bloodless given that both of Triceratops‘ brow horns have completely penetrated into Rexy’s leg. There’s a sort of ‘impact’ effect going on, and that’s it. Maybe it was to spare the kiddies blood and guts, but come on, now – kids love that stuff.

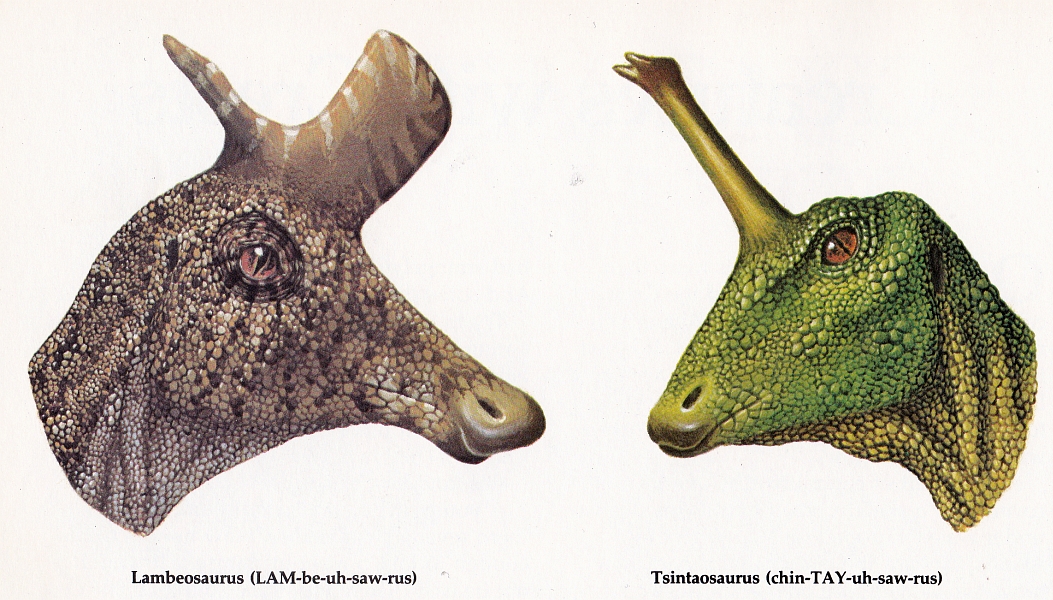

You know those photo-manipulations where someone’s taken a monitor lizard head, splodged it around a bit and added a couple of horns, and called it Albertosaurus? This is that, but in 1984, and entirely painted by hand. It is, therefore, considerably more impressive as I’m concerned, as the lizardy attributes had to be created from scratch on the page, rather than being already there. Still, these are some freaky portraits. Parasaurolophus, in particular, is the stuff of nightmares (while Tsintaosaurus is the stuff of a very obscure fetish that is probably catered for on deviantArt).

Technically, though, this is very impressive stuff. The artist – Biruta Akerbergs (known as Biruta Akerbergs Hansen these days) – is another one of those extremely talented wildlife artists who was probably given a series of skulls to work with, but very little direction otherwise. The results may be misguidedly lizardy, but appear almost disturbingly convincing with it.

Biruta Akerbergs Hansen also contributed this wonderful Quetzalcoatlus which, for the time, really isn’t all that bad. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that it’s actually rather good. It’s fuzzy, it has pteroid bones, and it isn’t an emaciated flying mummy. It also has a reasonably large toothless head on the end of its neck, and so avoids being a pin-headed toothy nightmare monster. I’m mostly including it because it dates from a time when the animal was still very poorly known, and so represents an interesting little bit of history. It could’ve been worse, John – a lot worse.

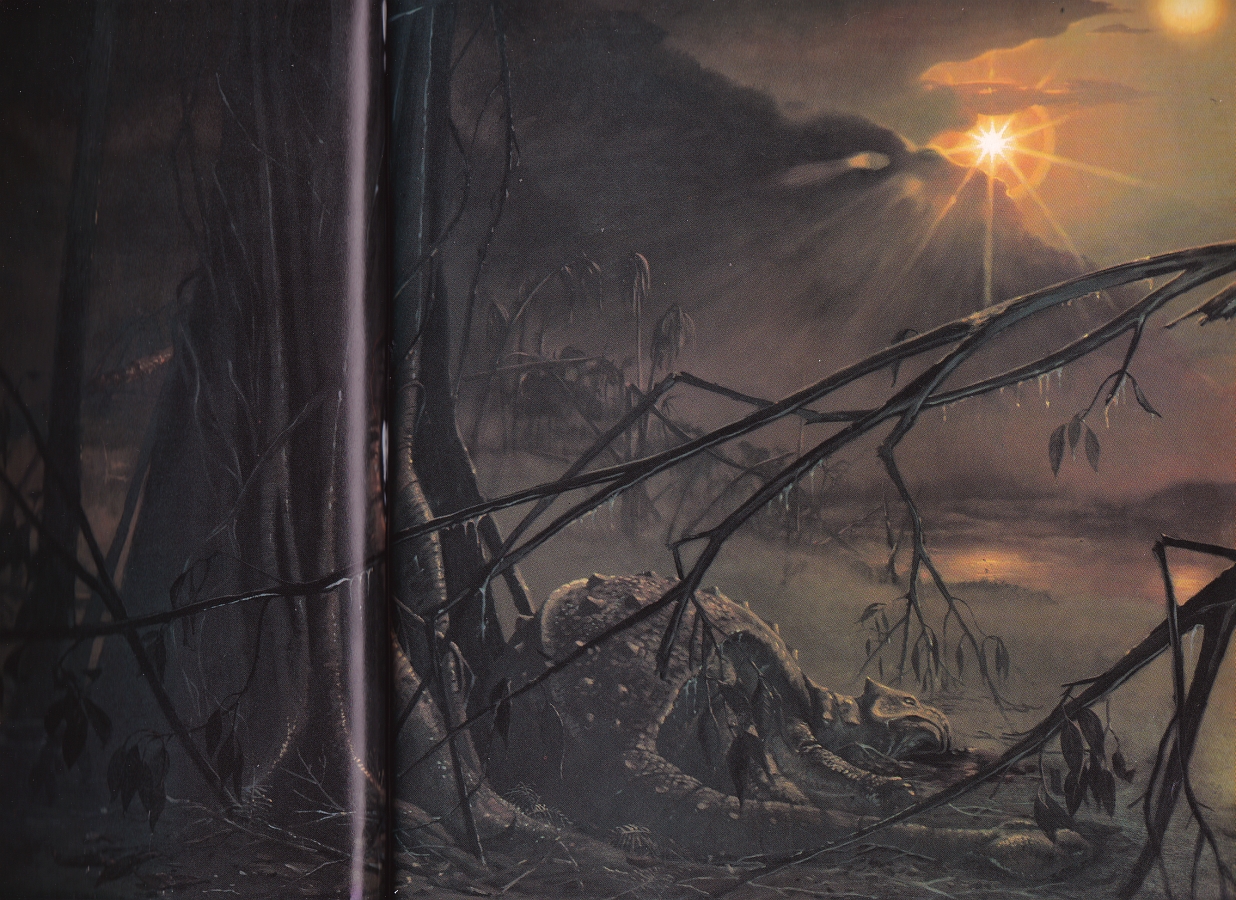

And finally…here’s a Kish piece that isn’t seen so often. The reproduction in the book isn’t fantastic (and then I had to scan it), but it’s still a stunning window onto a bleak, dark, chilling world, where the once-mighty masters of antiquity have been reduced to hollowed-out carcasses littering the barren, frozen landscape. The wilting trees in the background are a superb touch; while the focus is on one small patch of forest, this is somehow a more complete depiction of a planet-wide ecological catastrophe than many artists have managed. What a talent Ely Kish was.

Thanks again to Herman Diaz for sending me this one – my plan is to next review another book he posted to me, which also happens to be one David took a brief look at years ago…

2 Comments

implord66

June 28, 2020 at 7:07 pmI’m reminded of the Nile monitor lizard coloring in the protoceratops and velociraptor picture.

Pablo Lara

June 29, 2020 at 4:32 pmHi! Alex Ebel painted an interesting series of scenes of deep past, ( from paleozoic to Ice age)

“Childcraft – The How and Why Library” was published in Spanish as an encyclopedia by Salvat Editores.

Hispanic children knew about this book with the title of ” El Mundo de los Niños”, perhaps some folks from Spain and Latinamerica could remember it.

Do you have this book? I can search it in my library tomorrow.