Not for the first time, I’ve got hold of a book containing some very famous pieces of palaeoart and thought to myself ‘oh, of course these have been covered on the blog before’ – only to have a look and realise that they haven’t. In this case, I was sure that I’d reviewed The [London] Natural History Museum Book of Dinosaurs (from 1993) back when I first started writing for LITC. Nope! As a result, and in spite of John Sibbick’s art having been examined so often around these parts, some of his greatest work – that commissioned for the NHM’s dinosaur gallery, when it opened in the early ’90s – has yet to feature here. Well, it’s high time I rectified that.

Thanks are due this time to Herman Diaz, who sent me this and another book all the way from the States. He even threw a couple of lovely duck prints in for good measure. Thank you Herman!

My Favorite Dinosaurs was actually published in 2005, and therefore wouldn’t normally qualify for Vintage Dinosaur Art (due to the occasionally ignored 20-year rule). However, most of the artwork featured inside is rather older. One of the most interesting pieces in this book, for me, is actually the cover, as I don’t recognise any of the illustrations on it. Except for one, that is – the theropod on the top row looks very similar to an illustration of Yangchuanosaurus featured in an early issue of Dinosaurs!, which can now be seen in monochrome form on the NHM’s website. The Dinosaurs!/NHM version certainly doesn’t resemble Sibbick’s work (even if his style can occasionally shift), which makes me wonder if that artist copied some obscure Sibbick piece I’ve never seen, or Sibbick copied that artist. Where did the droopy-mouthed Yangchuanosaurus come from? I think we should be told.

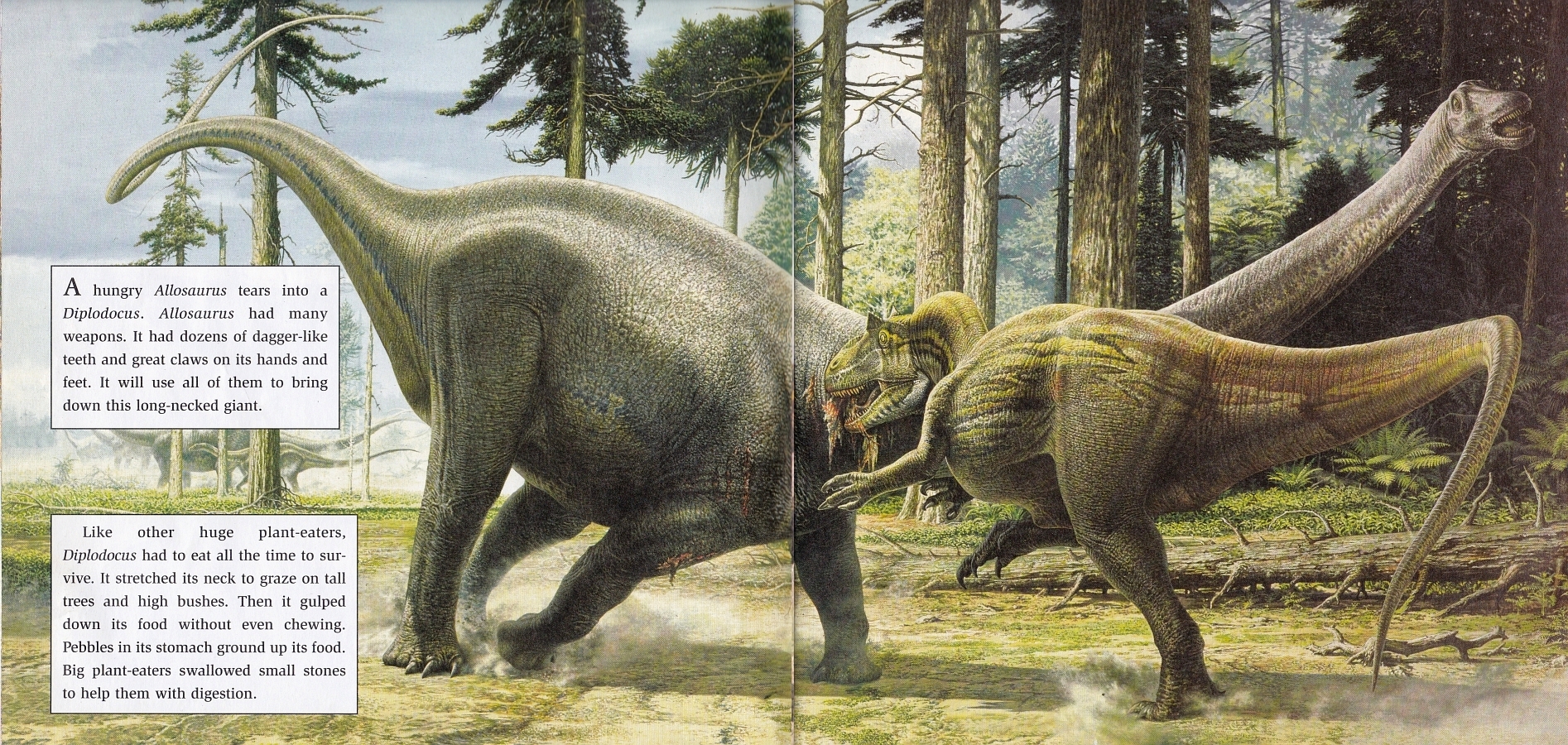

Now we’re talking – this piece will be instantly recognisable to, I’m quite sure, a large majority of our readers. One of the NHM commissions, it depicts an Allosaurus charging full tilt at a Diplodocus (a young Diplodocus by some accounts), savagely tearing into the herbivore’s flesh. This is a piece that demonstrates just how far Sibbick’s work had advanced since the Normanpedia, not even a decade prior. Gone are the tree-trunk limbs, shapeless bodies, and static poses found in that book. Both of these animals appear massive, but they are also muscular and active. Naturally, certain aspects of the animals’ anatomy would be drawn differently today, but this piece has aged impressively well. Unlike in almost every other artwork featured here, the theropod’s forelimbs are orientated correctly, while the sauropod has the correct number of claws on its feet (and the hands are concave). I’ve seen comments before that have remarked on how the Allosaurus’ pose here is slightly odd; at such a speed, why isn’t is slamming into its prey? However, given that allosaurs seemingly employed slashing bites, its position does make some sense. Unlike tyrannosaurs, these weren’t animals that would puncture deep into the flesh of their prey. They simply hadn’t evolved for that. This allosaur could be in the midst of inflicting a grazing blow with its jaws, not necessarily at the ideal angle, having sprung out and seized its opportunity.

This piece (and a handful of related works) must surely represent Sibbick at the top of his game. He was always good at making the animals in his illustrations appear convincing, even when they were anatomically dubious (not that they are so much here). As with other great palaeoartists with a hyper-realistic style, like Mark Hallett, it’s the small details that make it. The subtle sagging of the skin on the Diplodocus’ neck. The whiplike curve of the Allosaurus’ tail. And especially, the perfectly poised raised right foot of the allosaur. Even if you’re not necessarily a Sibbick fan, this surely must be acknowledged as an all-time palaeoart great.

There’s a lot of tension here, too. This is no placid herbivore succumbing to an unstoppable predator, Zallinger-style, even if it may appear that way at first. The Diplodocus is much larger than its attacker, and a swipe from its arm or neck could easily knock the allosaur off its feet. How will this end? It’s up to the viewer to imagine…

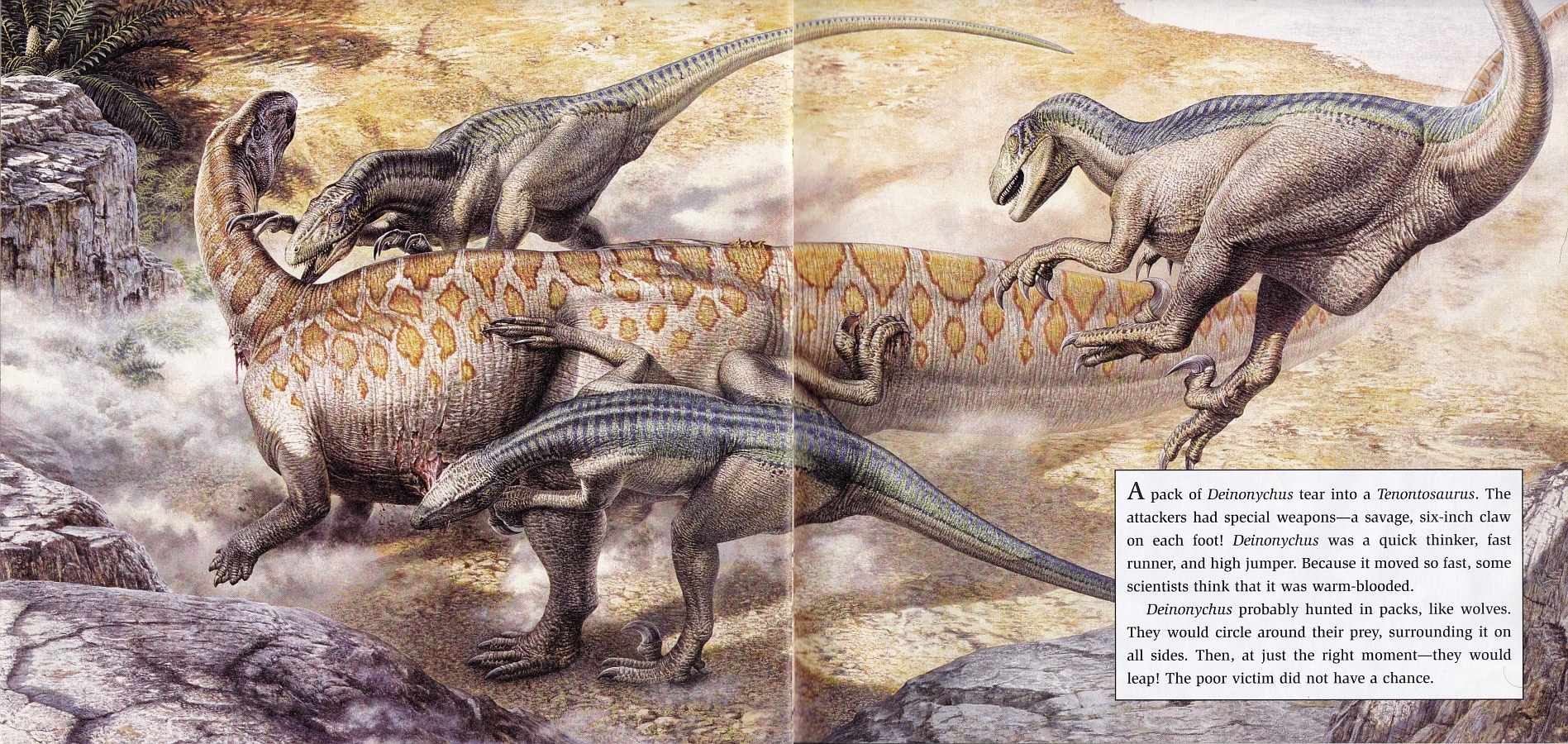

Because Science Marches On, some early ’90s Sibbick pieces have, naturally, not aged quite as well as others. This particularly applies to those featuring animals that were widely thought to have been scaly at the time, but are now known to have been extensively feathered. You know, like Deinonychus. This is still a highly impressive work of art, of course, and vastly better than many depictions of dromaeosaurs from that time. (I think there might also be an ornithopod in there somewhere.) Sibbick has always been very adept at making predatory animals’ sharp claws look utterly evil – never mind the sickle claws here (which might even have an undersized keratin sheath), just check out the hand claws on the individual at the back. Brrrr.

Furthermore, while depicting dinosaurs as having largely dull brown-grey bodies with brightly coloured highlights might be something of a Sibbick trope, the stripy blue-green backs on these Deinoncyhus are quite seriously groovy. Someone needs to work a similar idea into a modern, feathered depiction. Please.

I also feel obliged to point out that, yes, the Deinonychus in the centre has definitely just dislocated its leg. Before someone in the comments does. But never mind that, just look at these things – although we know now that such scaly depictions were wide off the mark, Sibbick still manages to make them look so real.

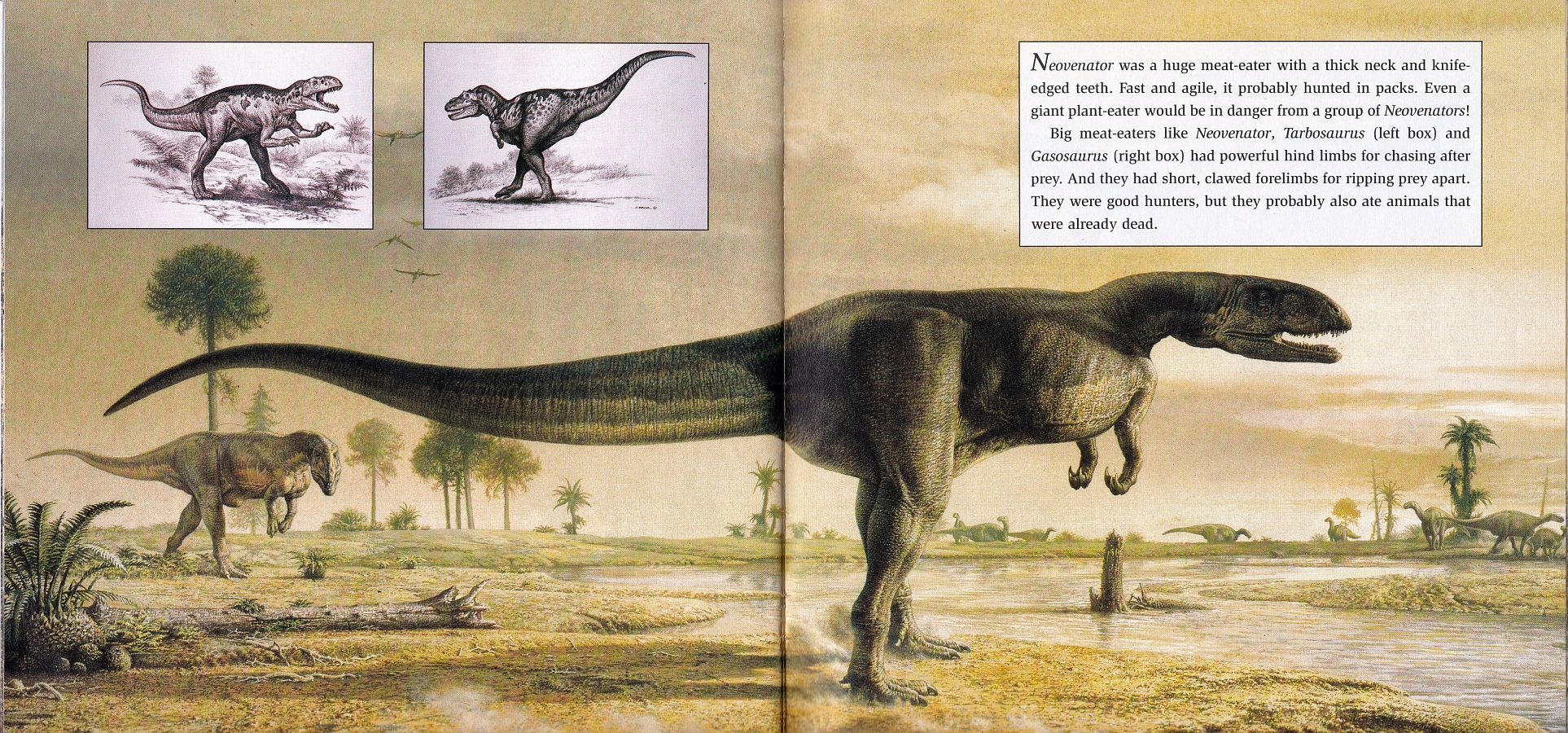

On to something ever-so-slightly more recent, now. The theropod depicted here is Neovenator, an allosauroid from the Isle of Wight, described in 1996. This Early Cretaceous animal has proven to be more interesting than it first appeared, as it resembles the much larger, later carcharodontosaurs in some respects, and lived alongside everyone’s favourite stabby-thumbed behemoth Iguanodon bernissartensis. Sibbick’s reconstruction here (produced in the late ’90s, I believe) is obviously dated in some respects, notably the pronated forearms and overly ‘smooth’ skull (it was later found to have typically allosaurian ridges). However, it’s stood the test of time well in many respects. When Scott Hartman published a skeletal in 2013, he left the following comment on DeviantArt:

“I feel like I owe an apology to John Sibbick – back when this painting [above] came out I remember thinking “no theropod looks like that”, but actually the general proportions are pretty spot on, even the crazy neck angle (no comment on the 3/4 view version in the background).”

Regardless of the individual shown in the background (a minor feature here, really), it’s impressive that this reconstruction managed to weather so well, oddly-angled neck and all. I love the lighting, too, and minor details ranging from the animal’s birdlike feet to its convincingly icy, slightly stupid stare. Incidentally, I drew my own version back in 1996, coloured in with felt pens. It’s probably not going to make it into a future volume of Dinosaur Art.

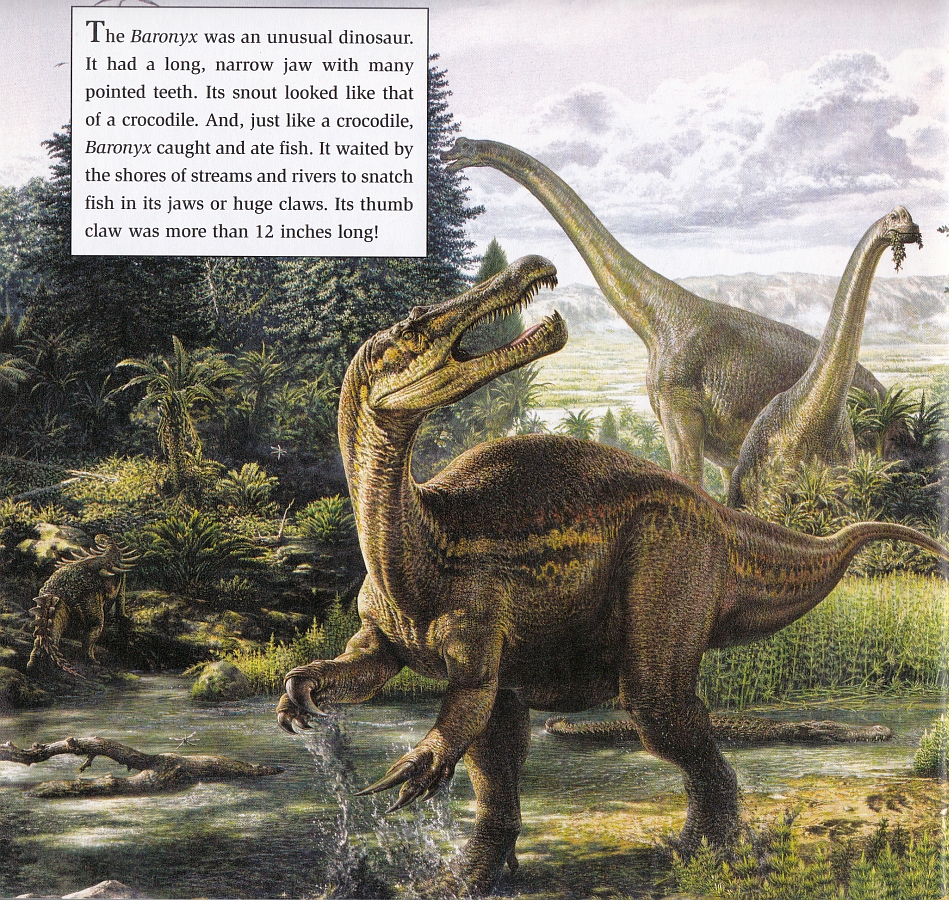

If memory serves, this illustration of Baryonyx (and friends) is also from the 1990s; the Normanpedia-esque appearance of the Polacanthus in the background would certainly suggest that. Certain details of this reconstruction would be different if it were painted today (the head would probably be shallower towards the rear, for example, a la Scott Hartman’s skeletal), in light of further spinosaur discoveries. All the same, this remains a beautiful piece that has aged quite gracefully. There’s a surprising variety of animal and plant life on show here – more than first meets the eye, and it’s always lovely when a piece rewards further inspection. This would make a great poster (cue comments pointing out that it’s already been turned into a poster).

Here’s an unusual one. This T. rex illustration lacks the usual Sibbick polish, and having seen exhibitions of his work before, I’d say there’s a good chance that it’s a ‘proof of concept’ or a developmental piece. Particularly notable is that it lacks a background to speak of. The pose of the tyrannosaur biting into the hadrosaur is certainly very familiar, and I can’t help but feel that this piece represents a stage in the development of something else. If any readers are able to fill me in, I’d really appreciate it.

The slightly odd-looking tyrannosaurs in the top right have been featured before. They remain slightly odd-looking.

Archaeopteryx! You’ve probably seen this illustration about 300 times before. It has a rather old-school feel about it, not that I can quite put my finger on why. It may be the bright colours, the head, the insistence on outspread wings, or some combination of the above. Regardless, we are at least given a properly feathered animal, with long fingers supporting its feathers; no cute ‘wings – but with hands!’ mini fingers on show here. Sibbick appears to know how birds work.

Ah – but what’s this? Why, those will be further feathered dinosaurs from Sibbick. The dromaeosaur in the top right (identified here as Dromaeosaurus, but I’m not sure that it’s supposed to be) was the first of Sibbick’s feathered dinosaurs that I remember seeing back in the day, and after so many years of intricately detailed scaly reconstructions, it seemed deeply strange. It’s a little dated these days, of course, but still nowhere near as bad as it might have been – the hands are facing each other and it does have a decent amount of fuzz, even if it’s apparently missing primary feathers. At the very least, it’s worth comparing these with his horrifying Normanpedia reconstructions, and marveling at how rapidly the science (and corresponding artwork) progressed.

Meanwhile, the animal depicted in the lower right is Protarchaeopteryx, which actually didn’t really have a great deal to do with Archaeopteryx, but never mind. It’s one of the more obscure of those tiny oviraptorosaur-thingies that BANDits get all hot and bothered over. Sibbick’s reconstruction appears well-proportioned, and drawn skillfully from a tricky front-on perspective, even if it is a little under-feathered. Still, we can put that down to the time in which it was produced (likely the late ’90s, as the animal was described in ’97). That tail fan is lovely regardless.

And finally…more feathers! No prizes for guessing that the top and middle illustrations here depict Sinosauropteryx and Caudipteryx, respectively. I really like this image of Sinosauropteryx as a small, fleet-footed, sharp-eyed little animal, casting a nervous glance over its shoulder as it clutches its prize closely. Caudipteryx, meanwhile, looks like it may have been given an unduly small head, but is otherwise well-proportioned, with primaries that connect to the correct finger, this time. Attractive colour scheme, too.

The lower illustration is perhaps most interesting here, as it is apparently a depiction of Microraptor. Now, I understand there was a lot of confusion as to how Microraptor should be restored in the early 2000s, and the occasional drastically under-feathered reconstruction did appear, but it seems odd that Sibbick would restore the animal with so little plumage. I’d be interested to know of the original context in which this illustration appeared (I’m guessing it was alongside the others here).

My Favourite Dinosaurs will return!

3 Comments

Zachary Miller

August 28, 2018 at 3:29 pmThe Microraptor is likely based on M. zhaoianus, the first species described. The fossil (V 12330) did not preserve much in the way of plumage. It wouldn’t be until three years later, in 2003, that M. gui was described. I believe all three species of Microraptor (zhaoianus, gui, and hanqingi) have been sunk into zhaoianus now.

David

August 29, 2018 at 11:39 pmLove these posts like you wouldn’t believe…but there just seems like there is little sense of discovery with this “newer” material. The more archaic, the more fascinating it reads.

Brian Choo

October 4, 2018 at 2:18 pmThe coverart originally appeared in Dinosaur! by David Norman (1991, Boxtree Ltd). This was the lavishly illustrated companion volume to the 1991 Granada/Satel television documentary series of the same name (the one narrated by Walter Cronkite) = https://imgur.com/a/Oj12PJv