There are certain books that you’ll be absolutely certain you’ve seen before, but just can’t quite place where or how. This was just such a book for me. T. R. (Tyrannosaurus rex) & Friends was published in 1988, and would’ve still been hanging around in bookshops when I first got into dinosaurs as a child, only 4 or so years later. When reader Elsie Swann sent over images from TR&F, the distinctive illustrations instantly rang a bell, but I didn’t recognise the title at all. Well, it turns out – and thanks to Rob Theodore over on Facebook for mentioning it – that the same book was published in the UK as The Sainsbury’s Book of Dinosaurs. Oh yes – back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, British supermarket chain Sainsbury’s dabbled in publishing and churned out a fair number of children’s books (I’ve still got their book on space and The Night Before Christmas). While Elsie’s edition is from the US, it mentions first being published by Walker Books in the UK – perhaps in its Sainsbury’s guise? Whatever the case, this is a wonderful, obscure kids’ book filled with technically accomplished artwork that is by turns impressive, hilarious and downright strange. And there’s a tiger in Africa. More on that in a bit…

TR&F was written by Rupert Matthews, with artwork by Tudor Humphries. Humphries is a highly accomplished artist and illustrator, with a huge catalogue of beautiful work to his name. Of course, I’m going to ignore all that and pick apart that dinosaur thing he did back in the ’80s, because I’m horrid. Inevitably, the cover of both TR&F and its Sainsbury’s incarnation is dominated by a huge, stripy rendition of the eponymous King of the Dinosaurs. (With apologies to Heinrich.) It’s an interesting portrayal of Rexy in that it appears to share a few peculiarities with others from the late ’80s and early ’90s, particularly in being quite dynamic and active, and having a well-observed head, but also a neck that doesn’t really make any sense. See also: the brown Dorling Kindersley model from the time. What’s with that neck?

But never mind. Other than that, there’s no denying that this strikingly stripy Rexy makes for a seriously impressive cover. Humphries also makes it appear massive and muscular, and other than perhaps having slightly shapeless lower legs, it strikes a good balance between elephantine heft and birdlike dynamism. The skin textures are great, too.

There are also other dinosaurs on the cover, of course. But again, we’ll get to those…

…Right away! Inside, we’re treated to the full spread that was adapted for the cover. While some of these animals lived tens of millions of years apart from their immediate next-door neighbours in this scene, this is almost certainly intended to be a Normanpedia-style depiction of related animals across time (and it just looks neater that they have a landscape to stand on). We’ve talked about Rexy already, so what of some of the others? Well, the Ceratosaurus pair have definitely been copied from somewhere, but my memory fails me (help in the comments, please!). The AMNH-style Allosaurus looks very dandy in bright red, but also rather dessicated. Coelurus and Coelophysis are competently done, and really just pleased to be here. And by far the most interesting out of all them are Oviraptor and Velociraptor, especially the latter. The Oviraptor is shown in typically ’80s scaly, nose-horned guise, albeit poised in a rather birdlike fashion (complete with cute little feather tuft). It also has a wonderfully vibrant colour scheme and stunning patterning, not unlike Rexy himself.

The Velociraptor, meanwhile, is deeply odd. The tricky perspective certainly hasn’t helped its bizarre anatomy, but the deeply wrinkly neck, tough-looking bumpy back, and flailing left arm are very strange indeed. Actually, this very scaly, saggy, ‘reptilian’ vision of a dromaeosaur is rather typical of the time, when artists who were paying attention clearly found it hard to reconcile the animals’ highly birdlike frames with the prevalent ideas about coelurosaurian theropods. At best, they ended up looking ‘plucked’, and much of the time, well…they just ended up looking hideous. I remember it well.

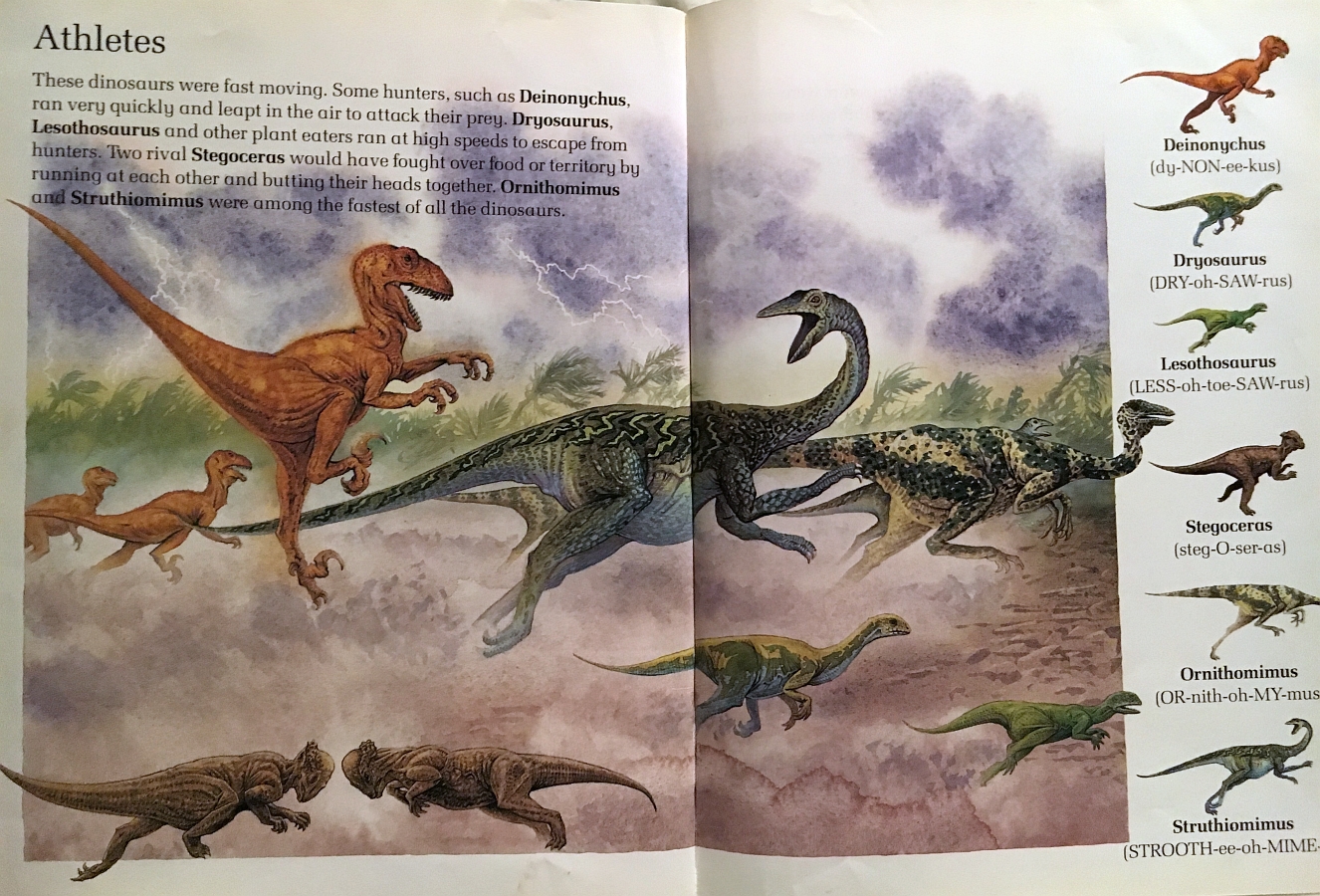

When ’80s scaly dromaeosaurs weren’t looking very strange and ever-so-slightly unsettling, they were more-or-less direct copies of Bakker’s Deinonychus. As seen here. I almost wish they weren’t here, because their familiarity detracts from what is otherwise quite a stunning piece – really beautifully painted and with ornithomimosaurs sporting fantastically vibrant, original, yet plausible skins. I’m particularly taken by the stripy, spotted, cryptic camouflage on the Ornithomimus – avoiding garish colours, believable, but still striking with it. Of course, it would be given feathers these days, but I’d still love to see patterns like this used more often on forest-living, scaly dinosaurs.

I know what else you’re thinking. Why is Stegoceras so tiny? You tell me.

Remarkably for a late ’80s dinosaur book, TR&F does contain at least one spread in which a group of herbivorous dinosaurs just sort of stand around, plucking gingerly at various plants. Whereas the book’s theropods are suitably active – running here, jumping there, baring their fangs and making a nuisance of themselves – the ‘plant eaters’ are rather staid and, well, retro-looking by comparison. A few of them are outright tail draggers (gasp!), while the rather lumpen Polacanthus would look at home in a Neave Parker painting. The Tsintaosaurus, meanwhile, is transparently a Sibbick Parasaurolophus with a cock-‘n’-balls head transplant. The watercolour work is great, and it’s all not too bad for the time, but we know that Humphries is capable of so much better.

Now this is more like it – that Gallimimus looks nothing short of fabulous. Skin that thing, and you could make a pair of shoes for a hopeless Prime Minister. (Seriously, though – that patterning is fantastic.) I also like that Stenoncychosaurus is threatening to devour the much earlier Compsognathus (again, while the anachronisms are deliberate, having them interact is fun). Staurikosaurus appears to have been coloured after those sour bottle-shaped bubblegum sweets but otherwise looks very gnarly, as do the two sauropods, one of which is – what else? – “Ultrasauros“. The inclusion of the good old chimeric behemoth is always a sweetly nostalgic treat. Something’s gone a bit wrong with Not Supersaurus‘ legs here, though. Similarly, the Mamenchisaurus appears to either have a lot of loose skin, or very stumpy little limbs. Hey, the former could be an interesting idea to apply to a sauropod reconstruction, I guess. Actually, didn’t someone already do that?

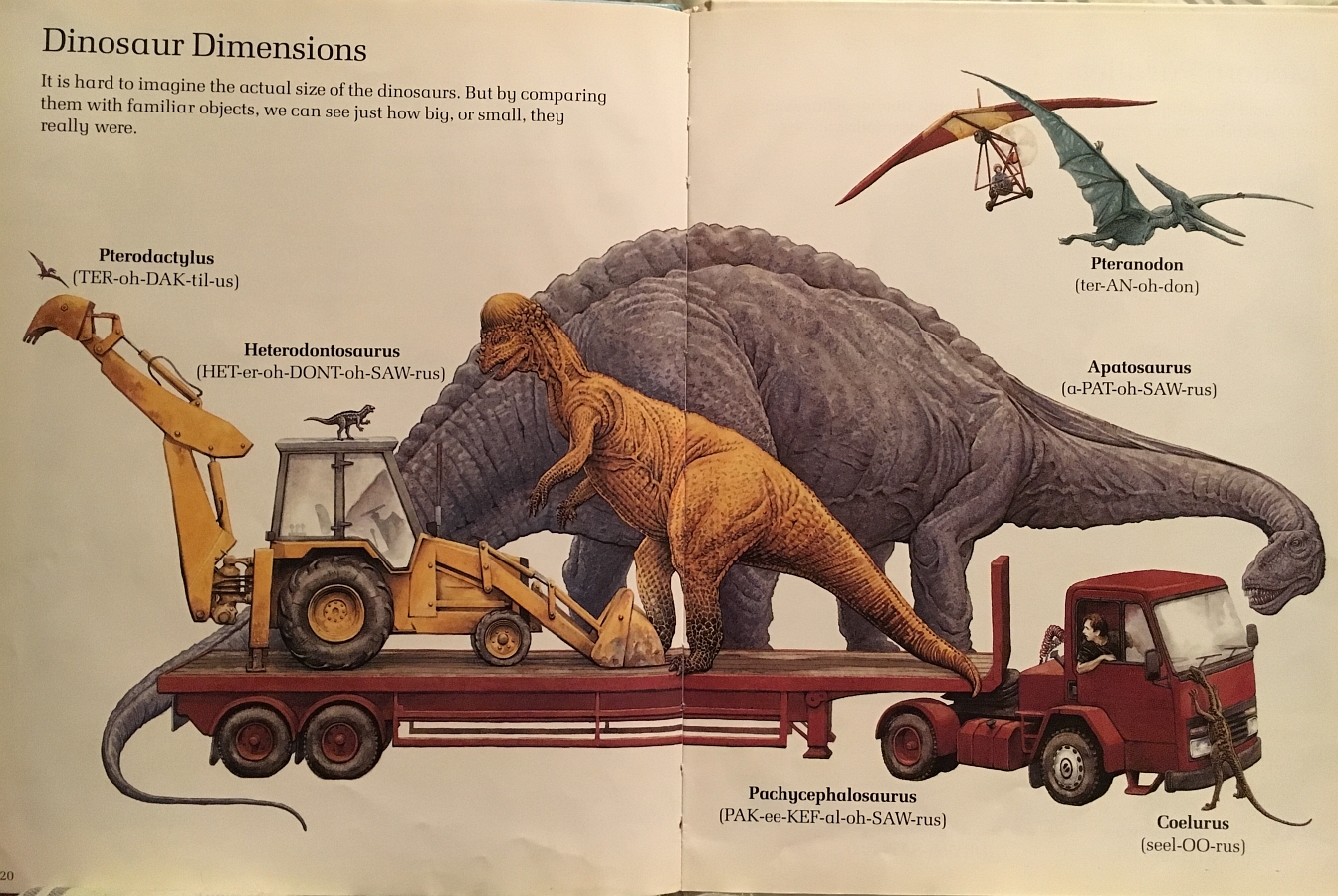

“Ultrasauros” might have been the biggest of all dinosaurs (in our 1988 vision of things), but other dinosaurs were pretty damn big too. How can we best visualise their voluminous fleshy magnitude? By comparing them with modern machinery, of course! As I’ve said before, I love these sorts of images – they really are the perfect way to hammer home the sheer size of these beasts to children, and they’re great fun to boot. We should perhaps address the fact first that, yes, that Pachycephalosaurus is quite improbably huge; but it was a commonly held view at the time. It also appears similar to the Dinamation robot. I’m quite sure that Pteranodon has been compared with a microlight elsewhere, but it’s still an enjoyable comparison, even if the Pteranodon appears to have hastily fixed-up bat wings. The real behemoth here – Apatosaurus – looks like an old-school ‘great fossil lizard’ at first glance, but on closer inspection shows signs of alarming Kishian skininess, with thin-looking skin hanging over worryingly protruding bones, at least in the torso region. It’s a weird mix.

And speaking of a weird mix…here are some pterosaurs. And also Archaeopteryx, because it’s contractually obliged to be here. I do like the inclusion of a spectacular foggy canyon for these pterosaurs to fly through, rather than merely having them float over the ocean, but there’s no getting away from that fascinating Quetzalcoatlus. This book is from a time when a long-necked, but tiny-headed Quetzalcoatlus was something of a palaeoart meme, seemingly arising from Giovanni Caselli’s deliberately vague illustration in The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs. This was all discussed at length by Darren Naish back in 2013, in a TetZoo article that’s now sadly been stripped of images by the good people at Scientific American. Unlike the ‘toothy nightmare monsters’ that feature(d) in Darren’s article, Humphries’ Quetzalcoatlus does appear to have a toothless beak, which makes it look rather like an angry, demonic swan. Aside from that, the Dimorphodon is also notable for being very freaky-looking in a Burian sort of way, and not appearing to have any legs to speak of. Poor old Dimorphodon.

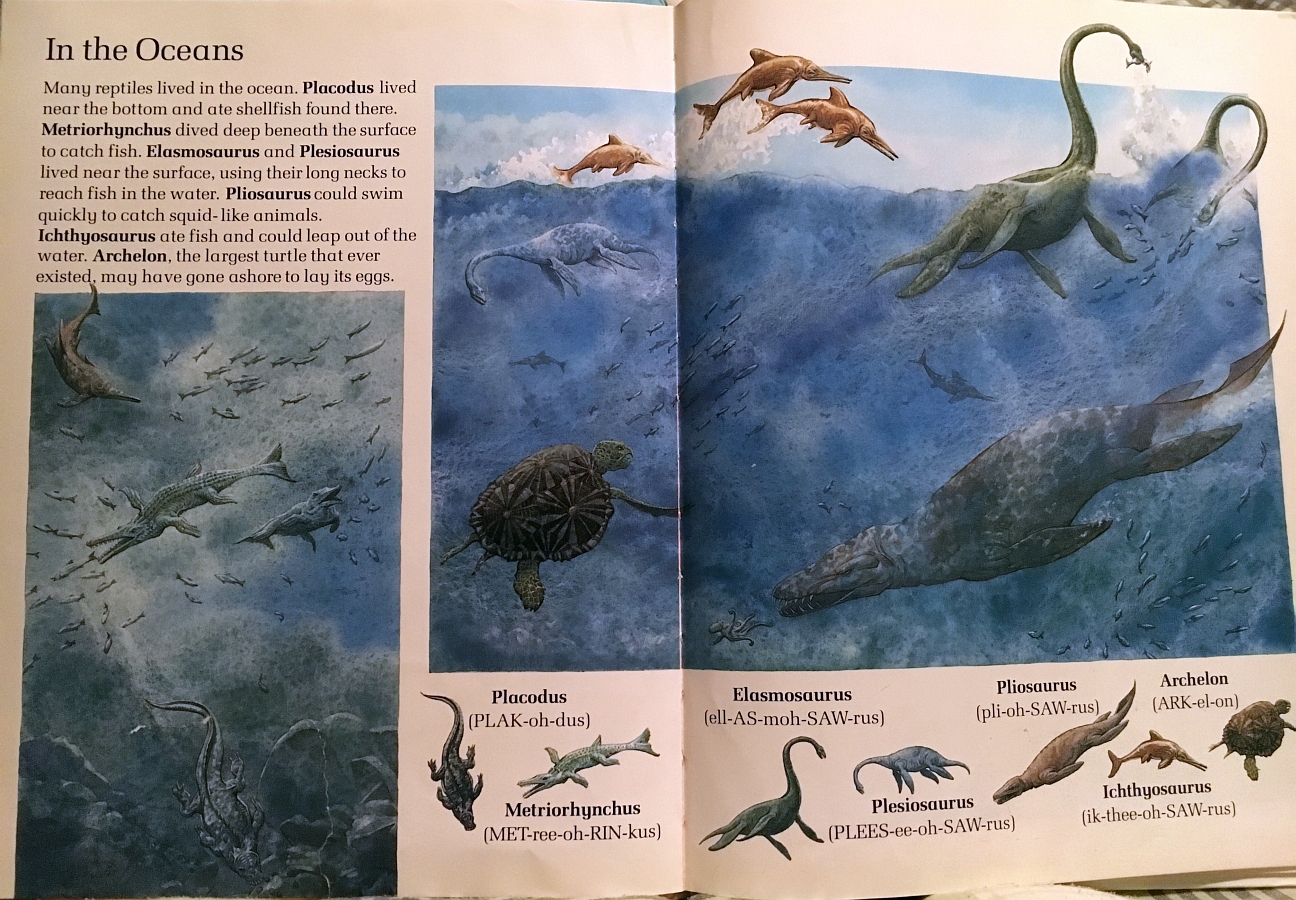

We’ve had our pterosaurs, so it’s surely time for some marine reptiles. You bet. Unusually, this spread is split into two distinct frames, although the animals in each still lived millions of years apart. It’s likely that there simply wasn’t room to convey surface waters and the ocean depths in the same scene. While the Elasmosaurus may be doing their classic swan-necked thing, it’s noteworthy that Pliosaurus has a soft tissue tail fin. Oh yes. A happy coincidence? Probably, but it hints at a certain intuition on the part of Humphries. The sinister Pliosaurus does remind me of an equally scary illustration that appeared in Dinosaurs!, and now I’m wondering about the origin of this particular look.

Whatever the case may be there, you’ve got to admire Humphries’ technique when it comes to painting the water itself. It’d be so easy just to slather on a great quantity of dark blue paint and call it a day, but Humphries creates churning water columns, full of fish, bubbles, sediment and who knows what else. He really creates an image of the ocean as a teeming, vibrant ecosystem where so many artists only manage to produce an image of a shapeless void. I told you ‘e woz skilled.

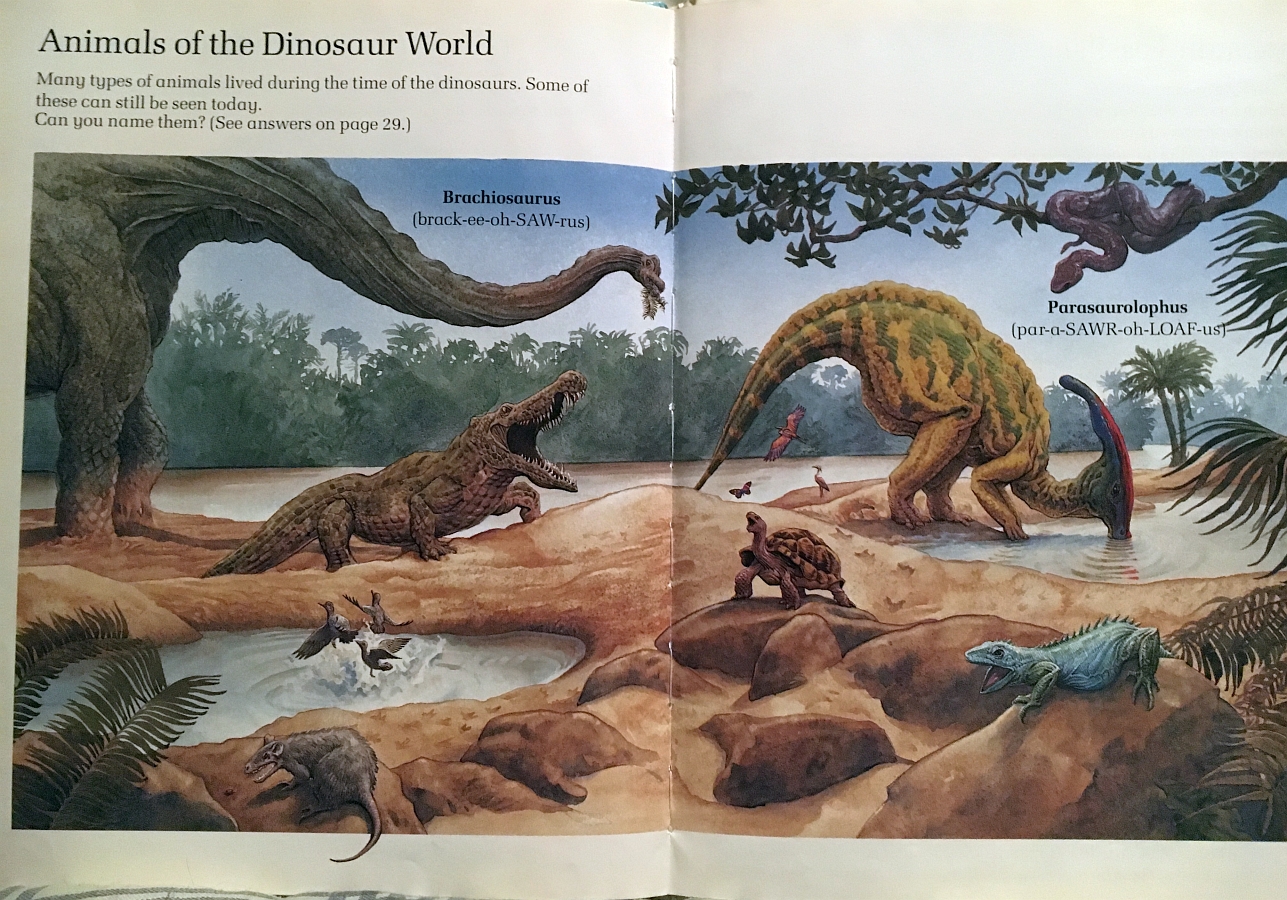

Aside from pterosaurs and marine reptiles, there were otherprehistoricanimals that lived alongside the dinosaurs. No one really cares about them (that’s right…NO ONE), but they stuff the vaults of natural history museums throughout the world all the same. You’ll be happy to hear that the creatures featured here aren’t just generic stand-ins based on modern animals…mostly. The crocodylian is Leidyosuchus, from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, the mammaly-thing is Morganucodon from the Late Triassic, while the snake is Madtsoia, from the Late Cretaceous in at least some parts of the world. The tortoise is, er, Testudo (just don’t ask), and the lizard and birds are generic. Not too bad. The birds look lovely, and I really like the massive thighs on the Parasaurolophus, which – much like Humphries’ T. rex – manages to look hefty and convincingly fleshy without being an old-school lardarse. The Brachiosaurus, on the other hand, is plain weird. What’s with that ridged neck? It looks like it’s being wrung out to dry. Make it stop.

I bet you didn’t even notice the cute interaction between the tortoise and a butterfly. You could write a whole kids’ book around that.

And finally…dinosaurs might look dead strange, but in many respects they were similar to animals living today. Some were tall and had long necks, like today’s giraffes, to reach the parts of plants that rival herbivores couldn’t get close to. Some were lightweight and fleet of foot, like modern gazelles. Some were small and devoured cute fluffy things, like jackals. And some inexplicably teleported into situations and places that they had no business interfering in, like African tigers, known to appear in a mysterious flash of light and unsuccessfully tackle rhinos by swatting at them. Wait, what? Yes, I know – the whole book’s full of scenes depicting animals that don’t belong together, and it’s quite deliberate. The same is true of the scene on the left here, where Albertosaurus, Triceratops, Ornitholestes and Dryosaurus all somehow exist in the same place. That’s fine, and in fact, the dinosaurs do look rather lovely in this scene; I’m fond of the stripy patterning on the Albertosaurus and weather-beaten look of the Triceratops. That Hallettish Saltasaurus is quite nice, too.

But the scene on the right depicts animals that all live in modern-day sub-Saharan Africa, except for that tiger. WHY IS THE TIGER THERE? Why not a lion? A lion would have filled the same role quite happily. It’s more boringly patterned, but at least a male would have had that spectacular mane. WHY A TIGER? It’s baffling, I tell you, totally baffling.

Never mind. Confusing tigers aside, this is a pleasing old book and a fine demonstration of Humphries’ skills as an artist; by 1988 standards, it’s actually rather decent. I’m now really hoping that the artist worked on other dinosaur books…in which case, you should watch this space.

6 Comments

Elsie

January 31, 2019 at 11:41 amI’m so glad you liked it! The size comparisons page was always one of my favorites as a kid, particularly the weird dopey expression on the apatosaur’s face.

Alexey Katz

February 6, 2019 at 11:54 pmI think that Ceratosaurus pair have been copied from two different Burian’s paintings (1941 and 1980).

Stepan Jindra

February 27, 2019 at 6:20 amYeah, Ceratosaurs positioning strongly resembles horizontaly inverted allosaurs from this work:

https://www.google.com/search?q=burian+allosaurus&safe=off&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiV_Kuk5dvgAhVDzoUKHevoBuUQ_AUIDigB&biw=1600&bih=757#imgrc=K-V0MAyAFQZHUM:

paleocharley

November 23, 2020 at 3:51 amI recognized the resemblance, but couldn’t find a picture on the Web. (It’s the “Allosaurus Belt Buckle” at the link above, although that only shows the left half of the full painting.) There was a very good reproduction in an encyclopedia set that I had as a kid. Apparently the original is at The American Museum of Natural History (NYC), but I can’t find the information about it in my notes.

Max Humphries

July 19, 2019 at 5:59 pmHey thanks for the neat write up, this is one of my Pa’s books. Fun fact: If you guys like puzzles you can find our family names hidden in the patterns of the Dinosaurs skin.

Chris

May 4, 2020 at 5:48 pmBeen looking for this for years. I had the Sainsbury’s version, haha.